Wheaton, Illinois, June 25, 1967

By Robert Walker

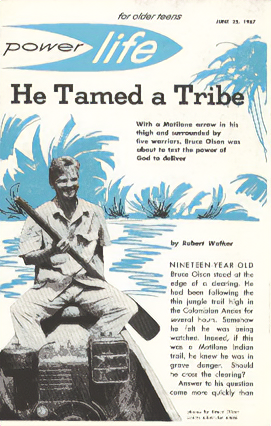

He [Touched] a Tribe

With a five-and-a-half-foot-long Motilone arrow in his thigh and surrounded by [twenty-]five warriors, Bruce Olson was about to test the power of God to deliver.NINETEEN-YEAR-OLD Bruce Olson stood at the edge of a clearing. He had been following the thin jungle trail high in the Colombian Andes for several hours. Somehow he felt he was being watched. Indeed, if this was a Motilone Indian trail, he knew he was in grave danger. Should he cross the clearing?

The answer to his question came more quickly than he anticipated. He heard the arrows, but could not see them until one struck him in the thigh. Dropped to the ground, he looked up into the faces of five fierce-appearing Indians with drawn bows.

They circled him, puncturing his skin—whether to torture him to death slowly or simply punish him for intruding on their territory, he could not be sure. Plainly, however, these were the Motilone Indians.

Bruce Olson is willing to admit that, in the face of the fear that knotted in his stomach at the moment, he was not then thankful to God. But hours later as a captive in a Motilone village, he expressed his gratitude to his heavenly Father for finally enabling him to find the Motilones.

The year was 1961. For Bruce, the trail to the Motilones had been a long and tortuous one. As a youth in Minneapolis, he had been converted to Christ in the Lutheran church of his parents. Yet it was not until one day in his senior year at school that he faced the challenge of total commitment to Jesus Christ as Lord.

He was seated in the school library. He realized it could mean the loss of friends, a promising career, wealth, and social prestige. As the minutes passed, Bruce struggled over his decision. Finally, he concluded that Christ must control his life.

During high school, Bruce studied Greek and Hebrew. After graduation, he enrolled briefly at the University of Pennsylvania and later audited classes in linguistics at the University of Michigan. But time was short. He believed God wanted him to tell people who had never heard the Gospel that Jesus Christ alone was the way to eternal life. He concluded that the Indians of South America would be the best candidates.

Both his parents and friends attempted to dissuade him, but Bruce could not be deterred. He bought a one-way ticket to Venezuela and landed in Caracas with only $70.

Because he was only 19 Bruce immediately ran into the problem of getting a permanent visa to remain in the country. Thoroughly discouraged, be sat down at a table in a restaurant one day. The restaurant was crowded and a man he had never seen before sat down at his table. Bruce explained his predicament, and his newfound friend offered to help, identifying himself as Roberto Irwin, private secretary to Rómulo Betancourt, then president of Venezuela.

But Bruce's troubles were far from over even when Irwin fulfilled his promise. For when he applied for a permit to contact Indian tribes in the remote jungles, his request was denied. Nothing he could do or say would avail. Missionaries simply were not wanted. But Bruce was convinced that God had not brought him this far to desert him. As he prayed, it seemed to him that he should contact his friend Irwin again. When Bruce did, Irwin introduced him to President Betancourt. When Betancourt heard his story, he authorized him to work with any aboriginal tribe he chose.

So, it was not long before Bruce packed and headed into the jungles. He was poorly prepared for the rigors of the trail. When the first night came he made a bed of leaves in the dark and tried to open a can of sardines. He had forgotten a can opener, so the best he could do was puncture the tin with a stone and drink the oil. For the next three days he wandered on and off the trail, until the afternoon of the third day when he topped a ridge and spotted a village in the valley below.

As he approached the village he shouted greetings in Spanish. Several old men came toward him, making sounds by running their fingers over their lips. How could he communicate with them? Then he pulled out a flute he had purchased in Caracas and began to play.

Immediately one of the men dived into a hut and drew out a flute made of bone. For the next six hours, Bruce learned the native tunes of the tribe.

That night Bruce was placed in their jail to await the return of the chief who was on a hunting expedition. The next day he learned these were Yuko Indians who already had been visited by missionaries.

By the time the chief and his warriors returned, Bruce had administered penicillin shots for an infection he had noted in some of the children and had won the affection of the older people in the village. As a result, he was allowed to remain in the village and learned to live like the Indians.

At the end of six months, he had learned a few Yuko words and formulated a plan for reaching the Motilones. He would move from one Yuko village to another in the direction of the Motilone territory. Because of the fierceness of the Motilones, he knew that on the last leg of his journey he would have to be on his own. No Yuko would enter the Motilone territory.

It was the following of his plan that had brought him to the clearing. Now with a Motilone arrow in his thigh and surrounded by five Motilone warriors, Bruce was again about to test the power of God to deliver.

The Motilones dragged Bruce to their village. As in the case of the Yukos, the tribal chief was on a hunting trip. It was plain to Bruce, however, that the majority favored killing him immediately.

That night he was stricken with amoebic dysentery, the deadly disease of the tropics. He diagnosed his own case and concluded that only God could heal him, for he had no medicine. Dysentery ravaged his body. By the second day he was so weak he found it difficult to walk.

The next night was a moonless one. Somehow it seemed to him he must try to get away. Once more he called upon God for strength. Late that night he was able to slip out of the communal dwelling where he had been held, prisoner. In the darkness, he groped his way along the trail until he came to a river. Stumbling and falling and rising again, he waded upstream.

Five days later he reached the headwaters. Ten more tortuous days passed. He had eaten no food and had no idea how many miles he had traveled. Then he saw a clearing and stumbled into a settlement. From there he was rushed to the nearest town for medical help.

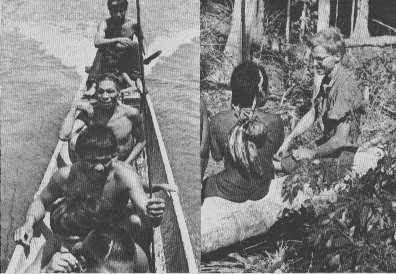

Within two weeks Bruce was back in the jungle headed for his Motilone Indians. This time he loaded a canoe with medical supplies and gifts. Eventually, he reached a beach where only a few months before the Motilone Indians had killed four fishermen and wounded five others. Pitching camp, he searched the jungle for trails. Finding several, he placed gifts on them.

Months passed and the gifts remained undisturbed. One day, however, they had disappeared and in their place Bruce found four arrows stuck in the ground. Oil company officials had warned him this meant “stop or be killed.” Confident that the Lord would watch over him, Bruce pushed on down the trail.

As he was chopping down a tree the next day he suddenly looked up and saw that a group of Indians had surrounded him. Their bows were drawn as bad been the case when the first Motilones had captured him. As they approached Bruce recognized one of them from the communal dwelling where he had been held. He gave the Motilone greeting, a lift of the eyebrows, and a nod of the head. Immediately the Indian smiled, spoke to the others, and they withdrew the arrows from their bows.

Bruce was taken to the Motilone village and allowed to run free. Carefully he studied their language, writing down words and phrases when he believed he had their meanings. Occasionally he discovered how mistaken he had been. On one occasion he kept repeating a phrase which he later learned meant that he was asking to be taken to the great chief of the Motilones who demanded death on the sight of all white men. The Indians had refused. But finally, they agreed and it was too late for Bruce to retract.

Four days along the trail Bruce developed a serious case of hepatitis. As he became weaker the Indians took turns carrying him. By the time they reached the village of the chief Bruce was nearly unconscious.

The chief ordered him immediately killed. But the friendly Motilones argued, “There is no reason to kill him. He is half-dead already. Let him die if God wants him to die.” Bruce learned later that the worst thing that could happen to a Motilone is to die a natural death outside his own territory. Such a person is doomed and damned forever. Hence, the chief decided this should be Bruce's fate.

One day he heard excited shouts of the Indians outside of the hut where he lay. From what he could determine, the Indians were describing a vulture-like creature which was swooping over them. Moments later Olson heard the drone of an airplane.

Although his mind was dulled by pain, Bruce persuaded the Motilones to carry him out to the clearing. At his urging the Indians spread his plastic jungle tent with red lining out on top of the communal hut. Then they fled into the bush.

The plane proved to be a helicopter. After circling the clearing and spotting the plastic tent, the pilot lowered the plane to the ground. Out jumped a physician. The two men had decided to see what the famous Motilone territory looked like. Of all the immense territory over which they could have flown, God sent them to the exact spot where Bruce lay sick. Placing the young missionary into the helicopter, they headed toward a hospital. Again Bruce's recovery proved astonishing. Within a few weeks, he was on the trail again headed for Motilone territory. Five days later Bruce Olson—the man the Motilones had believed had been carried away by the giant vulture—walked back into their communal house. The Motilones shook their heads in disbelief. “This could not be the same man; it must be his spirit.”

In the months that followed Bruce won his way into the Motilone tribe. He learned to eat inch-long soft-skinned worms (a Motilone delicacy) by biting off their heads and sucking out the insides with a smack of his lips (to indicate his pleasure). He also mastered the art of pulling off the legs of the walnut-size beetles before cracking their backs like a nut and sucking out their insides.

His first confrontation with the witch doctor of the tribe—a woman—came during an epidemic of pink eye. Deliberately Bruce infected himself. When the witch doctor came to chant over the others Bruce asked for the same treatment. Everyone was worse the next day. Again the witch doctor came. By the third day, Bruce's eyes were swollen almost shut. As he watched the witch doctor, he could tell that she was using her strongest spell. Now was the time to try his plan.

Calling her over, he offered her a tube of Terramycin. “Put this in my eyes,” he said, “and see if it does any good.”

The next day Bruce's eyes were improved; the others worse. In 48 hours his eyes were completely healed. He suggested to the witch doctor that she try the Terramycin on the eyes of the others. She did and was acclaimed for her cure.

When the epidemic spread to other communal dwellings Bruce offered her the tube of Terramycin again. This time she didn't bother with her chants.

In much the same way Bruce helped the tribal chief. Bruce did not attempt to offer new foods to the Indians. Instead, he planted corn in a little patch of ground that he had cultivated away from the communal house. The Motilone Indians were the only known tribe in South America who did not grow corn. In fact, they had no word for corn in their language.

When the chief saw Bruce eating it, he asked what it was. After the chief had eaten it several times and had expressed his delight with it, Bruce suggested that he offer some seeds to his people and encourage them to plant them. When the chief did, his people hailed him as a great benefactor. Although Bruce did not get the credit himself, the chief became his friend and protector.

One day the chief and the witch doctor asked each other, “Why is this white one helping us with our people? When he came we tried to kill him. But everything he has done for us has been good. Does this good one have some message for us from the god of the great vulture bird that snatched him away, healed him, and then brought him back to us?”

These questions soon came to Bruce. Now the long hours he had spent sitting around the fire listening to the folklore began to bear fruit. He had gained a fair command of the language; he knew the folk stories. There was Dibo-dibo (God) and Iskoridida (heaven, or literally translated, faraway trial.)

Carefully Olson reconstructed their fireside stories for the Motilones. He pictured Dibo-dibo as so loving the Motilone that He wanted every one of them to live with Him. But because the Motilones stole and cheated and killed, God had to send His Son, Jesus Christ, to earth many years ago. Here He lived like a man and underwent all the hardships of the trail that every Indian experiences.

Then some wicked people, despite the many good things that Jesus did, killed Him. Because He was the Son of Dibo-dibo, however, God raised Him from the dead and took Him to Iskoridida.

Bruce pointed out to the Motilones: that if they would commit their lives to Dibo-dibo's Son, Jesus Christ, and try to please Him. He would always be with them on the trail no matter how great the danger.

About two years ago Bruce Olson saw the first evidence of the Holy Spirit's work in the heart and life of a Motilone. Kobrydrá Bobarishora was the young man whose arrow first hit Bruce on the trail to the village. He had listened more intently to Bruce's story of the Gospel than the others.

Soon Bobarishora's actions evidenced a change in his thinking. “I have Jesus talk in my stomach and in my mouth,” he said. (The stomach is the center of emotions for the Motilone.)

Since Bobarishora's conversion, other Motilones also have “Jesus talk in their stomachs.”

Meanwhile, Bruce Olson, now 25, has continued to help Motilone tribal chiefs improve the physical life of their people. He has brought in domesticated chickens, turkeys, and sheep. In addition to corn and rice, he has taught them to cultivate coconut trees. As a result the Motilones, once a nomadic people forced to move about to locate food, now have settled down to a more happy and healthy life.

Bruce Olson insists, however, that the prosperous future of the Motilones does not depend upon these material advantages. Rather it is the lives of the born-again Christians who will ensure the physical health and material welfare and—above all, an eternity with Christ for the Motilones.