The Motilone (Barí) Miracle

A Christian missionary to be proud of...

By Faith Annette Sand

Normal noises filled the jungle afternoon—cicadas beginning to announce that evening wasn't far off, birds singing then sweeping over the river in pursuit of fish attracted by lazy flies. The monkeys were out of eyesight, but you could hear them chattering in the tall trees just beyond the clearing.

The changing of the guard from diurnal crew to nocturnal gang was definitely underway when the putt-putt of a motor broke through the idyllic green. I turned to Jairo, my fifteen-year-old Motilone guide, and asked, “Does that sound like the Iquiacarora boat coming upstream?” He thought it did.

I hurried to the river landing and watched the long dugout round the bend and get larger on the horizon. As it approached, I saw one blond head—the head of the person I was looking for—seated amidst a dozen black-haired people. I waved at the boat as it came alongside the landing, and the Motilone pilot deftly turned the canoe towards the shore.

Bruce Olson had been a hard person to find. After flying over the Andes to Cúcuta, a town in northern Colombia on the Venezuelan border, I had boarded one of those buses where suitcases are loaded on top while pigs and chickens come inside with their owners. We bumped five hours over washboard roads before arriving in Tibú, an oil town whose dusty streets are slicked down with a refinery by-product. (It keeps the dust from flying—but makes every step a trifle precarious.)

In Tibú, the Motilones maintain a large house where any tribal member can stay while being treated at the oil company's hospital. I had been telephoning this house for days, trying to get some information on Bruce's whereabouts. Each time, however, I had found myself speaking Spanish to a woman who understood only Motilone.

Finally, hoping to do better with sign language, I decided to make the trip to Tibú anyway. And to my relief, when the Motilone woman came to the gate, she smiled broadly—and went to call Jairo, a bilingual high school student who had just arrived from the jungles.

Jairo not only spoke good Spanish; he knew Bruce's itinerary. Best of all, he was willing to guide me to where he thought we could intercept Bruce the next day. I would find him on the river, said Jairo, making his circuit, visiting the villages, tending the sick.

Unfortunately, the pickup I needed to ride in for the next leg of the trip made only one trip a day—at six in the morning. Bright and early, Jairo and I crowded into the back end of the '42 Ford, which featured a plank down each side for first-class seating. (The unlucky hung on behind or dangled off the running board.)

The road followed an oil pipeline, which headed into the interior in a pretty straight line, up and down very hilly terrain. The Andes were nowhere in sight, but it was easy to see that we were on their tropical foothills.

After a breezy four-and-a-half-hour ride, we came to the River of Gold (named by some hopeful explorer). There we hired a Colombian boat to take us upriver another two and a half hours, where we were dropped at the home of a Motilone. It was there, in that idyllic jungle setting, that I waited to see how accurate the jungle telegraph really was.

As Bruce stepped out of the dugout to shack my hands, I felt like an accomplished scout who had just flushed a long-sought prize from its jungle habitat. I wanted to say, “Dr. Livingston, I presume?”—but I wasn't sure he'd understand.

The disparity between Bruce's tall Nordic frame, and the short, sturdy indigenous Motilones was the first thing I noticed. Yet his ease in communication with them and their naturalness with him somehow made him fit into their world.

“You feel like a Motilone to me,” I said as we walked toward the house.

“I will never really be a Motilone,” he answered. “I will always be different from them. Yet I know I will never again feel fully comfortable in the culture where I was raised.”

After having spent eighteen years in Latin America, I could relate to these feelings. To become a missionary is to give up not only the homeland but also the feeling of belonging in the homeland.

And the Motilone are certainly an admirable people to give yourself to. They are calm, soft-spoken, curious, and exceptionally gentle with their children. They are also generous and pleasingly content with their rather primitive existence. Bruce, I found, had taken on many of these Motilone characteristics in the two decades he had lived with them.

After that first meeting, we talked for nine hours nonstop. We talked through supper, through a one-and-a-half-hour boat ride to Iquiacarora, and for many hours after. Sitting in front of a clinic he helped establish, watching the full moon make its way across the sky, Bruce told me the story of how he came to work with the Motilone tribe.

Later he invited me to accompany him for a few days as he made his rounds, to give me a better feel for the Motilones and their world. I eagerly accepted, wanting to see for myself the amazing success this dedicated Christian missionary has had in helping to preserve the Motilones' traditional lifestyle while assisting them in a rather traumatic transition into the modern age.

The next day, Bruce and I waded through streams and squished along muddy jungle trails. Exotic vines dangled in our path, with thousands of varieties of orchids and flowers painting a serene beauty.

Yet in the midst of this beauty came the loud cries of tropical birds and screeching monkeys. Each of these creatures seemed to protest harshly our invasion of its turf.

As we plunged deeper into the Motilones' traditional land, I couldn't help but reflect on how much like the birds and animals of the jungle these indigenous people are. Living in amazing harmony with their tropical environment, they have been for four hundred and fifty years a territorial people. Following the laws of the jungle, they have done all in their power to keep foreigners off their turf.

Spanish conquistadores, dreaming of fabulous gold mines, made a mule trail through Motilone territory and established a settlement as a local power base. The ruins of a sixteenth-century Spanish chapel are still extant—a silent witness to how the cross accompanied the sword into the New World. (European churches are still filled with gold objects sacked from the indigenous peoples of Latin America.)

That the Motilones refused to be plundered is a testimony to their own feelings of self-worth. The Spaniards who settled in the Catatumbo River valley—which funnels water from the Andes down to oil-rich Lake Maracaibo—never made it back to Spain. They were massacred as they caravanned back to the coast. The gold bullion which they dropped has been swallowed by centuries of jungle growth.

The lesson of the Spanish invaders was never forgotten by the Motilones. They began killing everyone from the murderous and stealing “white” race who invaded their territory.

Until Bruce Olson.

It still isn't clear to them why they spared the life of this young Minnesotan who felt the so-called-of-God to bring them the message of Christ. Indeed, they shot him in the leg with an arrow when he first ventured onto their lands. But as a tall, gangly, blond youth, he didn't look much like a normal oil prospector or a Colombian land poacher. And he had a strong body which didn't succumb to the fever and infection which set in his leg.

Perhaps it was all part of God's providential care for the Motilone. Perhaps God knew that the tribe was reaching the end of its ability to fend off the invader. Their homeland was surrounded by Western oil companies, mineral prospectors, and land developers. People in the area remember how planes from the “outside world” firebombed the traditional Motilone longhouses, trying to force the Motilones to move off their oil-rich land. Remaining isolated and protected from the greedy outside world was no longer possible.

The Motilones, despite their cannibalistic reputation, are people who, at least in their exotic jungle environment, largely live at peace with each other. During his [thirty-eight] years with the tribe, Bruce has seen little homicide, drunkenness, prostitution, or physical violence. Not only do they have a true sense of belonging to one another in the community, but they also immensely enjoy life together in their habitat. Everything they do is made into a sport. Hunting, weaving, fishing, grinding, collecting the earth's produce—all of these become part of their happy modus vivendi.

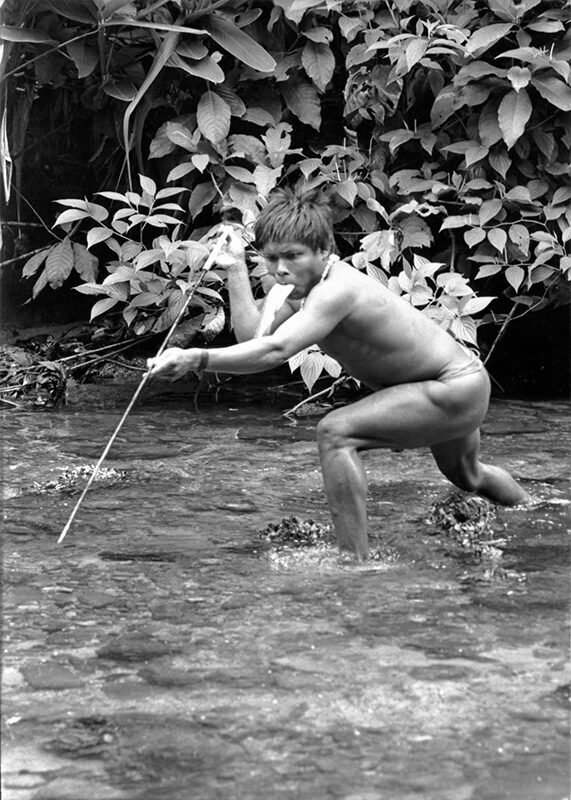

That first morning, for example, Bruce and I joined a group of Motilone on a nearby river. The early birds had enclosed a U-section of the river with a stone dam reinforced with broad leaves that looked like banana leaves, but much stronger. This gradually dropped the water level in the U, exposing the fish. The fish were speared with long, thin shafts which the Motilones sharpened after each thrust with knives held in their teeth. After a couple of hours, some men had fifty or sixty fish strung on their vines which they trailed in the cool water.

The day took on the feeling of a Fourth of July picnic. Children happily grubbed crabs under the rocks along the mud banks. Women collected and wrapped the fish in broad leaves for carrying home. And the men competed fiercely.

The celebration fervor seemed complete when the men decided to line up along the jungle trail—old men at the front on a handicap basis for a foot race home. (Chieftains in the tribe usually are the best hunters, fishers, and runners!)

During the dry season, these fishing expeditions occur three or four times a week. During the rainy season, the Motilones hunt with the same intensity. Incredible to think that every day is made into such a lark!

That day's fishing expedition, however, was marred somewhat, when a nine-year-old boy got too close to someone wielding a knife and was gashed in the leg. A sturdy young warrior carried the by piggyback to the clinic at Iquiacarora, where Bruce deftly put nine stitches in his leg.

“How do you account for all the skills you've managed to acquire without standard credentials?” I asked. “You've hardly even been to a university.”

“The Motilones were willing to accept me and knew I was here to help”, said Bruce. “And because I was the only one with any contact with the outside world, I felt obligated to read and observe and ask questions whenever and wherever I could so that I could provide the necessary services. Of course, it has been God who has helped me guided me, and taught me.”

Besides having the gift of truly enjoying their way of life, the Motilone are also religious people, concerned with pleasing God. Their mythology recounts how the knowledge of the trail that led them to God has been lost because of evil antecedents. Even before Bruce arrived, they knew they had broken communication with their Creator. And they knew they needed a special revelation to show them the way to the horizon where their God was to be found.

Some people consider the Motilones very lucky people. Or perhaps the Motilones have simply pleased God through their earnest desire to find the trail that would lead them back to their Creator.

In any case, God—who seems to prefer using the weak and foolish ones of this world to confound the wise—decided to send to the Motilones a lankly, nineteen-year-old, blond Scandinavian-American. Bruce Olson had no qualifications, at least none which would attract the attention of any established mission organization. But with the simplicity and trust of the young, this ingenious, half-trained linguist left college in the middle of his studies to head to Colombia. All he knew was that God had “called him” to go to the Motilones. (The story of how he was almost killed but then spared to live among the legendary tribe is recounted in his book Bruchko.)

When he first went to South America, Bruce's well-to-do family and various mission organizations expressed distress at his intentions. He was told he had neither the education nor the experience to prepare him for such a venture. And when Bruce responded that he knew God was leading him to do this, they were angered by his insolence..

Today, [thirty-eight years later,] Bruce has become a legend. What amazes missiologists is that countless missionaries around the world are being accused of destroying indigenous cultures or of making tribal peoples objects of idle curiosity. Yet someone like Bruce, with so little anthropological, theological, and cross-cultural training, has done so many things so correctly! (Seldom do the “called” pan out so well.)

Personally, I wonder if in this case, his lack of preparation didn't help. Bruce was able to enter Motilone territory without preconceived or traditional ideas on how to go about evangelizing a tribal people. Of necessity, he had to be sensitive to the tribe and its culture—and sensitive to the leading of the Holy Spirit.

While most missionaries learn a second language as a functional tool, Bruce learned his as a linguist—with a love for language itself. (In fact, by nineteen he was already fluent in English, Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. Since then, he's mastered eleven more.) Because the Motilone language is so difficult and because there were no primers, Bruce could only live among them—not jump in with all the answers. For the two years before he could really communicate, he learned to appreciate and respect them as a people.

Too many missionaries, Bruce feels, come with pride, technology, and a set understanding of the gospel—ready to show the people something. In contrast, he knows he has learned as much from the Motilones as they have from him, which precludes any feelings of superiority on his part.

Perhaps because of that, what he has been able to accomplish as a catalyst or organizer has been phenomenal. Not only has he communicated the message of Christ to these people within the context of their own images and myths. But he has done it in such a way that the entire tribe—happy to know of the Messenger who came to Earth to show them the path back to their Creator—decided to follow Jesus Christ.

Rather than try to “preach” to the entire tribe, Bruce concentrated on communicating the gospel to his “pact brother,” Bobarishora or “Bobby.” His prayer was that Christ would show himself to this people as a Motilone. So Bruce explained the gospel to Bobby in terms which Bobby could understand.

To find God, said Bruce to Bobby, you have to walk on God's trail. But God's Son, Jesus, is the only one who can show us God's trail. So we must tie our hammock strings into Christ and suspend all our weight on God.

After Bobby made the decision to walk in Jesus' path, he went to a tribal Arrow Festival. There he sang to the assembly in the Motilone's age-old method of relating legends, stories, and news. When he finished the fourteen-hour song, the entire tribe (in what anthropologists call a “people movement”) decided they wanted Christ to lead them over the horizon to where God was to be found.

Because the Motilones found Christ within their traditional ways, they have been able to preserve their tribal integrity while accepting a revolutionary new concept. This same pattern, with Bruce's help, has occurred in other areas of their life as well.

From the United States to the Amazon and from the African plains to the Australian outback, indigenous people are being systematically pushed off their homelands—and robbed of all they possess. Yet Bruce Olson and the Motilones have managed to preserve 95 percent of their traditional land in Colombia—83,000 hectares.

And they have developed [twenty-six] tribal centers on their reservation, each about a day's walk from one to the other. [Forty-two] graduate nurses staff each center's clinic. Vaccination and preventive medicine programs have almost controlled TB and measles epidemics—a perennial problem among indigenous peoples.

The Motilone population, estimated at forty-five thousand at the turn of the century, was down to a low of three thousand when Bruce arrived. Now the tribe is growing again—and estimated at about five thousand people.

Bruce has also promoted a cooperative of the Motilone people in the river valley. The cooperative has five goals: developing tropical agriculture, managing a farm store, providing medicine for the Motilone clinics, supporting the [twenty] bilingual schools established in the area, and providing necessary advocacy with the government to protect tribal rights.

The cooperative brings together [two hundred] Motilone families and [sixty] Colombian farm families who also live in the area. The cooperative has created a bridge between these once warring factions. And it has allowed them to be not only self-governing but more equitable in their local business transactions.

The co-op's main cash crop is cacao [chocolate]. A few years ago, Bruce began some grafting and developed a hybrid which doubles the size—and value—of the native bean. This provides the tribe with the necessary income for purchasing selected modern products.

Bruce himself is a traditionalist who would prefer to see the Motilones live in isolation in their thatched longhouses. But once [several of the] chieftains and the tribal families firmly decided they wanted to live in cement block houses, he organized and raised money for the cause. Today, [many] Motilones, [some] even in remote areas, hang their hammocks from composition roofed, screened-in, cement-block houses.

Hygienically, Bruce agrees, the new houses have their advantages. The thatch structures were impossible to keep free of cockroaches and free of all those little animals the tropics breed so abundantly. The concrete houses also allow for the isolation of TB patients and those with contagious diseases, helping to prevent the epidemics which tend to rage through these communities every three to four years.

Bruce encourages each community to keep one longhouse for its meetings and to preserve that tradition among the tribe.

Currently, the tribe has [five] hundred students studying in its own bilingual grade schools. Another [forty] students, all on scholarships, live in Bucaramanga and attend secondary schools and universities.

The advanced students spend their vacations at home, catching up on the skills and ways of their tribe, which they miss by being outside the tribe so much. The wisdom of this is readily apparent. The tribe needs lawyers, nurses, and doctors to act as buffers against those who covet its land. Yet the Motilones would never respect a male member who didn't know how to hunt, fish and run. Nor would they respect a female member who didn't know how to weave, garden, and prepare traditional foods.

The Motilones are an intelligent people, and all the motors and modern accouterments are now run and maintained by the tribe. I watched the pilot of our dugout canoe as he skillfully handled the outboard motor, moving the long, narrow tree trunk carrying fourteen people through white water rapids and the shallow river. He was serene, watchful, smooth in his movements, and exact in his judgments. It was easy to see him in the pilot's seat of a jumbo jet, handling that task with equal aplomb.

The Motilone has named Bruce Yado, which means “Rising Sun.” They chose the name, they said, because of the light he has brought to their tribe.

Yado, however, is a strange mixture of a man. He is gentle, tender, and friendly. Yet he displays an iron will and steely solidarity with the Motilone people. Winsome, yet opinionated, he takes a firm and determined stance in the face of all authority. The convictions of a crusader sent to do God's will, he is not moderated by the opinions of established institutions.

For that reason... certain Protestant missionaries [feel] he has [fallen short in the faith by] not instituting traditional Western forms of Christianity.

The entire tribe considers itself committed to following Christ [in death and resurrection] to the horizon. And Bruce has translated the entire New Testament into the Motilone language. Yet the tribe has no formal expression of its faith. Eight celibate young men, who are avoiding certain food [and liberties], currently are being trained as [spiritual] priests, in the general manner of Motilone customs. But the tribe has no “churches, no Sunday morning services”—[the Motilone believing community is a “church”].

One Motilone explained it to me saying, “Why should we sit in a line in a building for one hour each week to worship God, when I worship God daily walking the jungles, singing my song of faith? It is in the jungles that we expect to hear God. The wind of prophecy that rustles through the trees has always given us the answers of life, suffering, and death. [Every evening we read from Scriptures, and every community member comments on what Christ is teaching us—and how to align our lives with his compassion!”]

The outside world [accused] Bruce of either being a gold prospector, an emerald smuggler, or a man with a messianic complex—a true lose/lose situation. If he isn't in it for the money, he must be in it for the glory.

Bruce, however, has spent [thirty-eight] years enduring incredible hardships and isolation. Although physically strong, he has gone through bouts of malaria, dysentery, and hepatitis. The dreaded Chagas disease still periodically attacks his body, paralyzing and even blinding him for short periods of time.

Although Bruce is under the care of eminent tropical medicine experts, someday someone else will have to take over his job. And Bruce is preparing himself and the Motilone for that day.

In a world where indigenous peoples are so often robbed, murdered, and inundated by modern civilization, the story of the Motilone appears to be almost a miracle. Perhaps the work of Bruce Olson is a reminder. Perhaps it's a reminder for us all, that when the liberating, loving power of the gospel is truly released, justice, freedom, and hope can indeed prevail!