This is important to me. Please take a minute to watch this message. Also, I'm thinking of starting my Youtube channel to stay in touch with you. Tell me what do you think about this idea.

Written in Colombia

Translated from the Academic Quarterly 2024

Bogotá, Colombia, August 7, 2024

Academic Quarterly 2024

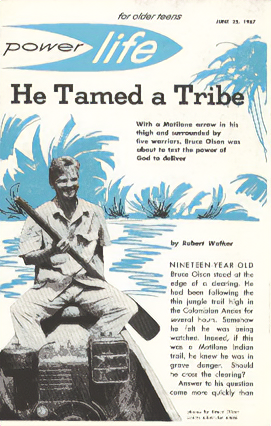

Bruce Olson's life journey, commencing at the youthful age of 19, is a captivating tale of faith, resilience, and unwavering devotion to serving humanity. Driven by an unyielding call from God, he ventured into the uncharted wilderness of Colombia in 1961, seeking to connect with the enigmatic Motilone/Barí tribe, renowned for their fierce nature and resistance to external influence.

Initially met with suspicion and hostility, Olson's unwavering perseverance and genuine desire to comprehend their unique customs gradually earned their trust and acceptance. The Barí, who affectionately called him "Bruchko," warmly embraced him into their community, forging an unbreakable bond that would shape the course of his life. He immersed himself in their language and culture, learning to communicate effectively and building bridges of understanding between their world and his own. This cross-cultural exchange laid the foundation for a remarkable transformation that would impact not only the Barí but also countless other indigenous communities across Colombia.

Olson's mission extended far beyond evangelism. Recognizing the tribe's lack of a written language, he spearheaded the development of a writing system for them, facilitating the monumental task of translating the Bible into their native tongue. This endeavor not only opened the door to a deeper understanding of Christian teachings but also empowered the Barí to document their rich cultural heritage, preserving their stories and traditions for future generations. By embracing their language and culture, Olson demonstrated a profound respect for their identity, fostering a sense of pride and ownership among the Barí.

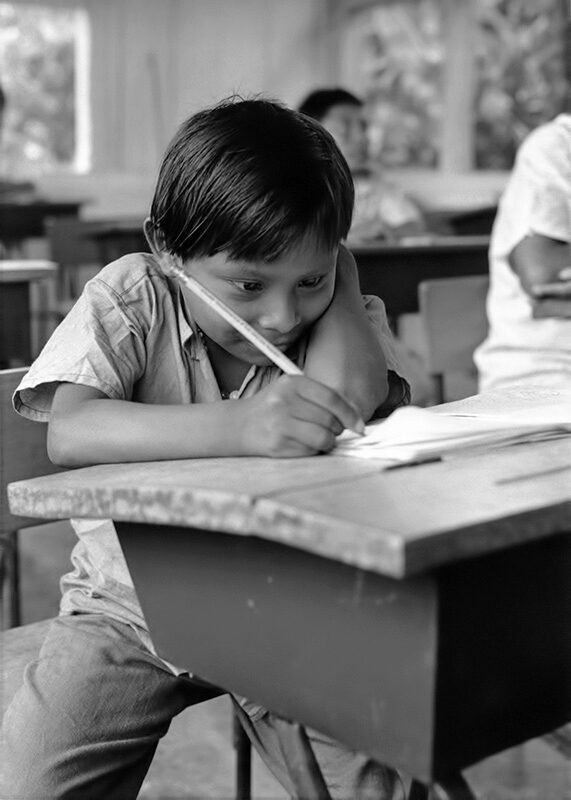

Education became another cornerstone of Olson's tireless efforts. He established schools in the heart of the jungle, offering young adults and eventually children a haven for learning and growth. His commitment to education bore fruit as many Barí youth went on to pursue higher studies in Colombian universities, ultimately returning to their communities as doctors, lawyers, and leaders, equipped to serve and uplift their people. This not only improved the tribe's quality of life but also fostered a sense of empowerment and agency within them, enabling them to advocate for their rights and interests in an ever-changing world.

Olson's compassion extended to the Barí’s health as well. He established medical clinics, bringing essential healthcare services to a population that had long been isolated and neglected. His tireless work in this area significantly improved the overall well-being of the tribe, combating disease and fostering healthier living conditions. This, in turn, strengthened their resilience and capacity to thrive in the face of adversity, ensuring a brighter future for generations to come.

Olson's path was not without its perils. He confronted threats from guerrilla groups and drug cartels vying for control over the region's resources and seeking to exploit its inhabitants. In 1988, he was taken captive by the National Liberation Army (ELN) and faced the dire prospect of execution. However, even in the face of such adversity, Olson's faith remained unshakable. He continued to share his beliefs with his captors, ultimately leaving an enduring impression on those who held him prisoner. Through divine intervention and international pressure, he was miraculously released, but his time in captivity had profoundly impacted both him and those he encountered. This harrowing experience solidified his resolve to continue his work and serve as a beacon of hope in a region plagued by violence and turmoil.

In the decades since, Olson's ministry has expanded to encompass 19 different tribes, encompassing a population of over 200,000 people. His approach, characterized by cultural sensitivity and a deep respect for indigenous traditions, has resonated with these communities, fostering an environment of trust and collaboration. His work has not only brought spiritual transformation but also tangible improvements in areas such as education, healthcare, and economic development. By empowering indigenous communities to take ownership of their future, Olson has created a lasting legacy that continues to bear fruit today.

Olson's legacy transcends individual heroism. It stands as a shining example of the transformative power of the Gospel and the significance of cultural understanding in bridging societal gaps. His life's work continues to inspire countless individuals to embrace their faith, pursue their passions, and dedicate themselves to the service of humanity.

Today, at 83 years young, Bruce Olson remains an active force in ministry, not only among the Barí but also among numerous other tribes in the Colombian jungles. He has become a revered figure, having addressed the United Nations and authored the bestselling book "Bruchko," which is now required reading in many missions organizations and Christian schools. His remarkable journey stands as a testament to the enduring power of faith, hope, and love in a world often marred by conflict and adversity. It is a story that continues to inspire and uplift, reminding us all of the profound impact one person can have when driven by a selfless commitment to serving others.

Your financial help (began from many since the 1960's) has transformed healthcare in the remote non-explored East Colombian River-Jungles and Headwaters. By organizing primitive schools for tribal youth, training local healthcare workers, and providing essential medical care, together we have empowered 19 indigenous tribes representing over two hundred thousand people. The graduation of 14 physicians from these communities is a testament to this lasting partnership and impact on education, spiritual values and healthcare in this undeserved region. Our most heartfelt and sincerest thanks!

From World Pulse, Wheaton, IL.

Final Analysis by Jim Reapsome ©1995

Bruce Olson's Legacy

When Bruce Olson and his mule ventured into Venezuela's uncharted jungles 40 years ago, ranchers drummed some common sense into him. “There are tame Indians and wild Indians,” they said, “so be sure you locate the former and not the latter.” But having never seen one, he was in no position to judge.

He had gone to Caracas to prepare for his mission to the Indians because while in high school he was convinced this was what God wanted him to do. While working for the government in the Ministry of Health and studying at the university, he saw the Motilones on God's compass.

One day in 1964 he came to our home with his jungle diary, and a couple of wicked-looking Motilone spears. I published his diary and those spears graced our walls for years. Our kids loved Bruce and his stories gripped them. So much so that when our daughter got married she asked for the Motilone spears. Now they've gone to Santiago, Chile.

On his first jungle trek, Bruce wandered around in circles for hours, stopped for the night, and discovered he had no machete, nor a tool to open his sardines. He sat down on the trail with his mule and decided that since the mule wasn't scared, he would be all right. Doing what he did was like launching a space shot to the moon. But look at the record of what God has done since Bruce and his mule set out from Machiques in the foothills of the Andes.

The so-called “wild” Indians have been transformed by the Lord Jesus Christ. Bruce has seen the work of the Holy Spirit continue to the next generation of Motilones. But they not only have redemption and new life, but they also have the technical preparation they need to survive on the lands of their forefathers. Their lands, by the way, are now protected legally, thanks in great measure to Bruce's tireless efforts on their behalf.

Tribal students are academic achievers—15 are studying in university, next year 13 will graduate from high school, 22 from vocational training, and 12 from the school of nursing. All the 400-plus previous Indian graduates are serving their tribes in the jungles. Not one has abandoned the jungle for city life. In the jungles, more than 2,500 students are getting bilingual education in 18 languages.

Bruce has built facilities and trained people to work in 18 health centers, 42 bilingual schools, 22 agricultural centers, and 11 trading posts, which really are co-operatives. They spark social development in places overlooked by the governments of Colombia and Venezuela. The co-operatives provide the economic base for 18 tribal peoples.

The director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for Northeast Colombia is a Motilone lawyer. The director of Indian Affairs for the state government is a Motilone graduate in business administration. The coordinator for press relations for Northeast Colombia Native Peoples' Affairs is a Motilone university graduate in journalism.

How has all this come about? Obedience, faith, courage, suffering, wisdom, and persistence by a young, unheralded missionary who did not bring Jesus to the Motilones as a foreign import but as one who sojourned their “trails of life's experiences.”

Today's missionaries, churches, and agencies should gorge on Bruce Olson's story like kids chomping on fresh-sliced watermelon. We need this story to reinforce our faith and to stir up the current crop of high school and college students. People in our churches need to know it because they are subjected to misleading propaganda about the failures of missionaries and how they have destroyed indigenous cultures. Bruce Olson's story is the best answer I know to people who gripe, “What's the point of sending missionaries?”

From Charisma and Christian Life Magazine, Lake Mary, FL.

HOSTAGE! PART ONE

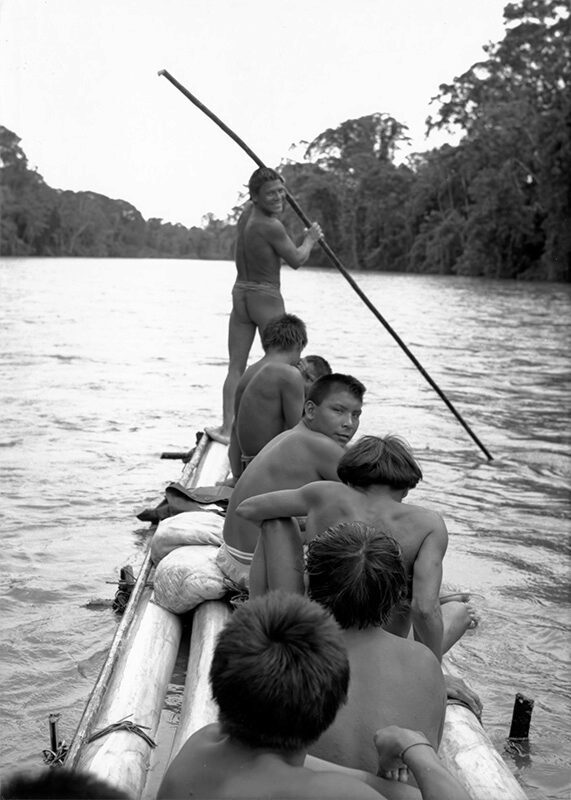

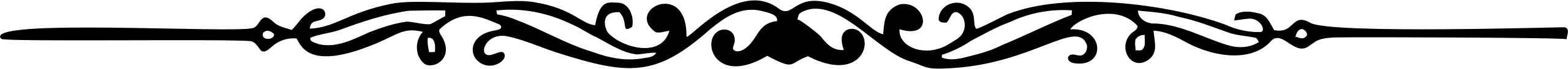

The hot sun beat down upon the equatorial jungles of northeastern Colombia known as “Motilandia.” It was a steamy, 100-degree October morning. Exotic birds screeched, monkeys screamed and a chorus of katydids assaulted my ears as I headed toward the dugout canoe that waited on the bank of the Rio de Oro to carry me and 15 Motilone Indian companions down-river from Iquiacarora to Saphadana, the site of a Motilone food cooperative. I walked slowly, enjoying the company of the Indians and savoring the sounds; of chattering jungle creatures in the lush greenery surrounding us. I was never in a hurry to leave Iquiacarora.

As I climbed into the canoe, I glanced at Kaymiyokba, one of the Motilone leaders who had become my close friend over the 28 years I'd lived and worked among his people. He grinned, starting up the outboard motor while the other Indians took their seats. His warm smile filled me with a deep sense of satisfaction and belonging. We were family, he and I. The people crowded around me were my brothers and sisters. I was truly at home and exactly where I belonged on planet earth. The thought filled me with a mixture of quiet contentment and nostalgia.

How could I have imagined, when I first walked into the jungles of Motilandia in 1961, all that God intended to do here? How was it possible at I had left my family and friends in Minnesota at the age of 19 to go on a journey that would lead to such an exotic place, and to these amazing, legendary people a —people so isolated and hostile that no white man had survived contact with them in 400 years of recorded history until I walked into their territory?

When I boarded the plane for South America with nothing but a one-way ticket and a few dollars in my pocket, not knowing one word of Spanish, nearly everyone had thought I was crazy—or just plain foolish. But I had been unable to resist the subtle, persistent longing that had drawn me here, the growing love that God had put in my heart for the indigenous tribal people of this continent, the quiet voice inside that told me I would never be happy, never have a moment's peace, until I obeyed His call. No, I could not have imagined where that call would take me; I could not have imagined that today my heart and my life would be deeply rooted in these people and in this vast, remote jungle.

Nor could I have imagined that this day, October 24, 1988, would be a day unlike any other that I had spent in these jungles, that it would be the first day of a 9-month ordeal that would leave me—and indeed, a whole nation—profoundly changed.

It was a good day for travel. The rainy season was upon us, but the sun had broken through and I was glad to see it, even though it would turn the jungles into a giant steam bath. I'd been feeling another malaria attack coming on, and the intense, sweltering heat of our down-river journey just might sweat it out of me—or at least keep my teeth from chattering for a while.

As Kaymiyokba steered the boat, I scanned the shorelines on both the Colombian and Venezuelan sides of the river, watching for any guerrillas who might be lurking there. The four major guerrilla organizations in Colombia had operated in adjacent territories for nearly 12 years, gradually controlling more and more of the area surrounding Motilandia. Guerrilla strategists were avid students of revolution in other parts of the world; the Sandinistas' failure to occupy and control Mosquito Indian tribal lands in Nicaragua had been a serious error, and Colombia's guerrilla strategists had learned from their mistake. My life had been threatened repeatedly because Colombian revolutionaries saw me as the key to controlling the vast Colombia-Venezuela border territory belonging to the Motilones. I was, in their eyes, so influential among the Motilones and other neighboring tribes that unless I could be convinced to join their revolutionary movement and bring the Indians into their cause, the Indians would be a constant thorn in their flesh. Since I had resisted their previous attempts to recruit me, I'd been marked for elimination. With me out of the picture, the guerrillas theorized, the Indians would soon yield to their demands. They would then have free rein in northeast Colombia—and the success of their revolution would be assured.

All of this had made me cautious in my journeys through areas like Saphadana, where the guerrillas seemed to be making their presence known with increasing boldness. I was not fearful for myself so much as I was fearful of the bloodshed that might result among the Indians if I were killed. The guerrillas were capable of anything. I had known many of them over the years, including some of their leaders—a surprising number of whom were former pastors, priests, and students from mission schools in the area. I had even tried to convince a few to redirect their idealism toward positive, humanitarian social service goals instead of revolution, but without much success. These were dedicated terrorists who had learned to rationalize their kidnappings, executions, bombings, and other crimes by claiming they served a higher cause: “The people's revolution.”

Now, as we journeyed downstream, I felt tense. Everyone else seemed in good spirits, so I tried to relax. After an hour and a half, I caught a glimpse of the shoreline at Saphadana, immediately noticing two guerrillas standing in a clearing a short distance from the boat dock. They carried rifles and machine guns, and they were watching us intently.

Victor, the Motilone sitting next to me, leaned over and whispered, “The guerrillas are looking at us.” He exchanged nervous glances with Kaymiyokba.

I avoided looking in the guerrillas' direction. While Kaymiyokba docked the canoe I deliberately turned my back on the guerrillas as they walked toward us. I was about to climb out of the canoe when, without warning, a spray of machine-gun fire pelted the water around us.

“Out of the canoe!” one of the guerrillas shouted. They were still about 30 yards away. We climbed out, and the Indians started toward the guerrillas, obviously intending to attack them with their bare hands. But one of the guerrillas fired another volley in our direction, this time slamming into the motor and ripping a gaping hole in the side of the canoe. “Lie down with your faces to the ground!” he ordered.

Kaymiyokba continued to walk toward the guerrillas. I could see that he was struggling to control his anger. “Let's discuss this,” he said in Spanish. “Let's not start something we'll all regret...”

“There's nothing to discuss!” the guerrilla shouted, spraying the dock area as punctuation. One of his bullets grazed Kaymiyokba's forehead. The Motilone stood his ground.

“Bruce Olson is taken captive by the Camilist Union-National Liberation Army!” the guerrilla shouted, motioning at me to step toward him. This guerrilla group, commonly known as the ELN, was the only one of the four largest national revolutionary organizations that had not agreed to an informal truce with the Colombian government after being offered the opportunity to put their agenda before the people in free elections.

I assessed our situation, realizing I had only a few seconds to make a decision. There was no way we could successfully resist these men in physical combat; I could safely assume there were more armed guerrillas hiding in the trees, and we had no weapons whatsoever, not even Motilone bows and arrows. I never carried arms, and on this trip I hadn't even brought along a pocket knife—not that it would have been any help against military weapons.

I quickly reviewed other possible options. I could jump in the river and swim underwater to avoid the guerrillas' bullets, and probably escape downstream. I knew the area very well; the guerrillas did not, so my chances would have been good. But that would have left the Motilones at their mercy, so I couldn't risk it. And it would only put off this moment to another time, another place.

As the guerrillas trained their guns on me, I decided that the moment had come to face the enemy. But I would try to do it on my terms, in a way that would catch the guerrillas off guard and give the Motilones their best chance to escape unharmed.

I picked up the backpack I'd dropped when the gunfire had started and told Kaymiyokba in Motilone, “Don't follow me! Don't do anything!”

Then I spoke to the guerrillas: “I'm Olson,” I said. “I'm the one you want. Leave the Motilones alone.” I turned and began to walk away from both the guerrillas and the Indians.

By the time I'd walked a few yards, about two dozen more guerrillas materialized out of the jungles. I ignored them and kept walking, hoping to put as much distance as I could between them and the Indians. Then someone shouted, “Stop! Stop or we'll shoot!”

I kept walking faster and faster, shouting at them over my shoulder, “You came to capture Olson. You can have me, but you'll have to come and get me!”

The guerrillas started after me and I began to walk as quickly as possible without actually running. Finally, when we were about 500 yards from the Motilones and all the guerrillas had abandoned the Indians to chase me, two more guerrillas suddenly appeared in front of me. Using their weapons, they knocked me to the ground and roughly forced my face into the wet earth. One of them put his gun to my head.

So this is how I'll die, I thought. A bullet through the brain. I was surprised that I felt rather calm.

As I waited for the trigger to be pulled, the other guerrillas arrived, all of them very nervous and excited. “He's very dangerous! Careful!” someone shouted. “Don't take any chances! Don't let him move!” Everyone talked at once, breathing hard, working fast. My hands were yanked behind me and bound tightly with a nylon rope. This is amazing, I thought. Who would believe this? They're afraid of me!

I was dragged to my feet and about 30 guerrillas closed ranks around me, ordering me to walk. I was relieved to find that we were headed away from the Motilones, who continued to watch from a distance, obeying my order to do nothing. I moved as quickly as possible, praying that they would not decide at the last moment to put up a fight. They didn't.

The guerrillas pushed me steadily through the wet, tortuous jungles, first on foot, then by canoe, and finally on foot again, for three days and nights until we arrived at a location they'd decided would make a relatively safe first camp. I knew exactly where we were most of the time; it was territory I'd traveled to many times during my 28 years in the region. I was thankful that if I had to be kidnapped, it would be here, on home turf. It would have been truly horrible, I thought, to be captured in a city, taken to a strange, unfamiliar place, and locked in a small room. At least here, in the high Catatumbo, I was in the place I loved more than any other spot on earth, the place I knew God wanted me to be.

If I had to die, this was where I wanted to do it. I wouldn't have a single regret. It was ironic: Here I was, in the hands of ruthless terrorists who were probably going to execute me shortly, and I was feeling quite pleased and comfortable with the situation because I knew—beyond all doubt—that I was exactly where I belonged at that moment. This certainty would stay with me throughout the ordeal to come.

In all of the 12 camps, I lived in during the nine months of my captivity, I would be guarded 24 hours a day by at least two heavily-armed men. The guards were usually changed every hour, so there was no possibility that one might fall asleep or become too relaxed in my presence. Much of the time my hands were kept bound behind my back, even when I was very ill and in extreme pain.

The rains were relentless and demoralizing. A crude makeshift shelter was constructed over my hammock in the first camp, but it offered virtually no protection from the elements. I was always soaking wet, even when the rain let up for a few hours, as it did only occasionally. It was so humid, even on sunny days, that shoes and clothes never could dry.

During the two weeks, I spent in the first camp, I tried to remain quiet and spend as much time as possible resting to give my body a chance to recover from malaria. But the attack continued and then, just as I thought I was recovering, came back again, probably as a result of the conditions I was living in. I knew malaria wouldn't kill me, but the disease has a way, sometimes, of making you almost wish it would. Yet it wasn't unbearable. I had learned years before, when I had injuries and illnesses in the jungles, to separate myself from the physical discomfort. When you're miles from help and your arm or leg is dislocated on a jungle trail, you can't sit down and agonize over it. You have to keep going. I'd say to myself in such moments, “I'm in pain, yes, but this pain only exists in my body. I am not my body. My mind and spirit are above this, not part of it.” This technique worked for me, and I would use it to get through some of the worst experiences of my captivity.

It may seem bizarre to some people, but the truth is that it never once occurred to me that it was God's responsibility to rescue me miraculously from this situation. Instead, I believed it was my responsibility to serve Him right where I was. What I asked of God from day to day was very simple, very practical, and I suppose quite typical of me: Father, I'm alive, and I want to use this time constructively. How can I be useful to You today?

This was to be my prayer, as well as my “strategy,” throughout the long months of my captivity. But it was nothing new; it was how I approached every day of my life. Why should my prayers or my outlook change now, just because I was in the hands of guerrillas? I knew that God was subtly orchestrating His plan in the jungles—not only among the Motilones and the other 14 tribes we'd been working with but also among the guerrillas. I assumed that this situation was part of that orchestration, and I wanted to be open to whatever God might have in mind. I've always felt that I could serve God in any situation, and this one was full of intriguing possibilities. As a result, I wasn't terrified or even particularly anxious about my fate. I knew it was God—not my captors—who would control the outcome of the situation.

When people ask me now, “How could you believe that God was in control when you were in such a horrible situation?” the best way I can answer is to tell a story about something that happened during my first years in the jungles when I was out with a Motilone hunting party.

Our intrusion into the jungles had brought the usual reaction from assorted birds and monkeys that day, but as we quietly slipped through the dense undergrowth I noticed a sudden escalation in the volume and intensity of the cacophony. Millions of katydids joined the animal squawks and screeches, raising the noise level to the point where our human voices were nearly drowned out. I'd never heard anything like it.

Astonished, I'd turned to a nearby Motilone and shouted, “Listen to that! Isn't it incredible?”

The Indian had nodded his agreement. “Yes,” he'd called back, “We heard it too. It's a piping turkey!”

His remark had stopped me in my tracks. A piping turkey? All I'd heard was chaotic, ear-shattering racket! How could anyone notice the voice of one lone turkey in the midst of this din?

The Motilone had seen my confusion and had signaled me to stop and listen quietly. When I did, it took several minutes before I began to pick out which sounds were which—animals, birds, insects, humans. Then, slowly, the separate voices became more and more distinct. Finally, after more patient listening, I heard it. Behind the hue and cry of the jungle, behind the voices of my companions, behind the quiet sound of my own breathing, was the haunting, reedy voice of the piping turkey, sounding for all the world like it was calling to us from inside a hollow tube.

It had been a poignant moment for me, a moment that had spoken to me of much more than the Motilones' highly developed sense of hearing and my own lack of auditory discrimination. It had made me wonder what I'd missed—not only in the jungles but in my own spiritual life. How much had I overlooked when I'd failed to patiently “tune in” to God's subtle voice in the midst of life's clamor and activity?

In the years that followed, the piping turkey had come to mind many times as I'd struggled to discern God's voice and sense his quiet, often barely detectable presence in the seemingly chaotic situations I encountered. But over time, I had learned enough patience to be able to see God in the subscripts of life. And I'd learned from experience that even when I couldn't see or hear what He was doing, I could trust that He was always there, always working out His sovereign will, even when I was too overwhelmed by the “noise” to notice or appreciate His complex orchestrations.

So it was natural for me when I was kidnapped, to assume that God was there, working in His usual way and that I was there for a purpose.

Of course, it also helped that I had been in this position before, and had seen what God could do in such an apparently impossible situation. When I'd walked into these jungles for the first time, some 28 years before, I'd been shot through the leg with a five-foot-long Motilone arrow and held captive for months in anticipation of execution. During those months, God had given me a love and compassion for my Indian captors far beyond anything I had ever expected. In the years since then, the entire tribe had become part of me—my closest friends as well as my brothers and sisters in Christ. Now I could not imagine life without them.

Yes, I had been captured again—but with a difference. These were new “enemies,” but I had been prepared by the experiences of 28 years for this challenge. It was reasonable, really, for me to assume that God might intend to do among the guerrillas something similar to what He had done among the Motilones. So the question was never, How could I believe that God was in control? The question was, How could l doubt it?

In the first guerrilla camp, I met with the national political director of the ELN, Manuel Perez, who explained my official status as a “political prisoner.” I'd known him eight years ago when he'd first invited me to work with him in the revolutionary movement. He was a former Jesuit priest, and I'd told him then that I believed Christians had no business killing people—even if it was, as the guerrillas claimed, necessary for the advancement of humanitarian goals, or to eliminate “enemies of the people.” I'd said that as Christians we really ought to be involved in social services, living the example of Christ, reconciling and saving lives—both physically and spiritually—not engaging in terrorism and bloodshed. I'd even urged him to get involved in the cooperative movement, which would benefit the poor farmers of Colombia whose cause he'd claimed to be championing. He'd seemed very interested in my ideas then; now, eight years later, we were sitting together in the jungles of the high Catatumbo region discussing his plans for a new Colombia.

“We want you to join us,” he told me. “We want you to organize health and social services, set up schools, do all the things you've done among the Indians. You'd be a part of our national leadership.”

I listened respectfully but noncommittally. I was to be detained for about two months, he explained, “for dialogue.” During that time I would meet with many guerrillas involved in social services so I could begin formulating a national strategy. He clearly couldn't imagine that I'd turn down the great honor he was offering. But just to give me an added nudge in the right direction, he made sure I understood my options: If I didn't join them, they'd kill me. As the days passed, I looked for ways to enter into the lives of the guerrillas, to understand their motivations, backgrounds, and strategies. I felt no animosity toward them. After all, who was I to judge the guerrillas? We were on an equal footing before Christ. My job, as I saw it, was not to “convert.” I knew that God would provide the means, so my plan—if you could call it that—was simply to live one day at a time and stay alert to small opportunities for bridge-building.

One such small opportunity came after only a few days in the first camp when I noticed that I wasn't the only one who was sick. Some of the guerrillas also had malaria, but others showed symptoms of hepatitis. As I observed the guerrillas' activities, I saw that their sanitation habits were contributing to the spread of the hepatitis virus. To put it bluntly, the guerrillas seemed to spit constantly, and their spittle contaminated the ground wherever they went. Eventually, this ended up in our water supply as well as in the food.

I mentioned this problem to the camp responsible—this was what the guerrillas called their officers—and like magic, the spitting stopped.

Not long after that, a different responsible named Arley came to me about another medical problem in the camp.

“I've been designated camp nurse,” Arley told me. “But I have no training.”

“I've trained nurses,” I told him. “Would you like me to teach you?”

He was an eager student, quickly picking up simple, basic nursing skills—points of injection for antibiotics, dosage calculations, drugs for common tropical diseases, and even a little dentistry. Guerrillas often needed to have teeth pulled. Arley took his responsibilities seriously, and I welcomed the opportunity to serve—and, of course, to build a relationship.

It was a beginning.

In the two months that followed, the guerrilla leaders tried everything they knew to draw me into their movement. They reminded me frequently that I would be executed if I didn't join them. I lived on a seesaw: One moment I was being treated almost kindly, and the next I'd be bombarded with abuse. I avoided argument, stayed away from the more volatile members of the group, and simply tried to serve—steadily, undramatically—in any way I could. I taught the cooks how to make delicious sauces out of smoked palm grubs, made bread for the whole camp three times a week, and wrote flowery love letters for illiterate young guerrillas to send to their girlfriends. It was amusing in more ways than one.

But I never forgot what would happen to me when the guerrillas finally realized that I could not be recruited into their ranks.

By January, I'd been moved to a third camp. I began to sit in on some of the guerrillas' daily political discussions. The first time I attended they got into an argument about terms and finally turned to me for an explanation of the differences between socialism and communism, dialectical materialism and democracy—concepts they'd been struggling with for some time. I gave them a fairly complete explanation of these and a number of other related concepts. They seemed fascinated. Afterward, several of them asked if I'd serve as their regular discussion leader.

I immediately spoke to the officer, called the responsable. “I'm worried,” I told him. “Am I talking too much? I didn't intend to usurp your authority. What shall I do?”

“It's only right.” he told me after giving it some thought, “that you should lead the discussions. You have the knowledge and education, and you don't impose your ideas on us. You stimulate discussion. It would help us. By all means, you must lead.”

So I became the discussion leader.

This naturally gave me an opportunity to introduce ideas that the guerrillas had never before heard. Many of them had grown up in the movement and had little or no schooling other than guerrilla classes in the jungles that exposed them only to the views of their pro-Castro revolutionary leaders. They enjoyed talking about social and economic theories they'd never been able to discuss with an educated “outsider” before. I resisted the temptation to give my own opinions except in a neutral way, choosing instead to answer their questions with more questions—always giving them credit for good sense and an ability to think for themselves. They responded enthusiastically.

The guerrillas began, after a time, to ask me about my motivations—and why I didn't hate them for “depriving me of my liberty,” as they described my kidnapping. They were curious about my personal and religious philosophies because I wasn't behaving the way they'd learned to expect captives to act. It was a chance for me to talk about my Christian faith, but something inside told me this was not the time to talk about such things. I'd learned to obey these inner impulses, knowing that when God gave them He had a reason. I also trusted God to let me know when the guerrillas were ready to hear what I had to say. So I simply responded to their persistent questions by saying, “It's a personal matter.” This seemed to make them more curious than ever.

As we got to know each other better, the younger guerrillas began calling me by a nickname that would be picked up by others as I moved from camp to camp: “Papa Bruchko.” The Motilones had originally dubbed me “Bruchko”—it was the way “Bruce Olson” sounded to them when they first heard it—but these young guerrillas jokingly added the “Papa” because at 47 I was old enough to be their father. I knew that many of their friendly gestures were an attempt to draw me into a feeling of comradeship so I'd want to join their organization, but that was all right. It made life a little easier and it cost me nothing.

As our group discussions continued, I soon recognized that most of the guerrillas were very poor readers. I enjoyed teaching, and it would build bridges with my captors, so I offered to set up an informal school to teach reading comprehension and writing skills. The responsables saw this as evidence that I was taking an interest in joining them, so they gave their wholehearted approval. Once the school was underway, we added basic studies in ecology, social and political sciences, history, and geography. The students were surprisingly eager to improve themselves, so it was satisfying for me.

Even many of the responsables attended classes. It was partly, no doubt, to monitor my teaching. But I was impressed with how serious most of the students were, even though you couldn't exactly call my classes “formal.”

One day, for example, I noticed one of the students—the top responsable in the camp—sitting off to one side during a class. While I talked, he ceremoniously pulled a long piece of elastic from one of his socks and began snapping at the giant ants that scurried around him on the ground. He was able to hit them with amazing accuracy. With each kill, the students around him murmured appreciatively. As I watched this performance I thought, He hasn't heard a word I've said. Maybe I should quit for today.

But a few minutes later the responsable looked up from his game and made an incisive, insightful comment that summed up my entire talk. He's understood everything I'd said and was even able to draw some complex conclusions from it. It taught me not to underestimate what went on in the minds of the guerrillas. They missed very little.

About five months into my captivity I was allowed to have a Bible. It became very precious to me. I had, of course, spent so much time translating the Scriptures into Motilone over the years that I'd committed most of the New Testament to memory. That had sustained me during the early months of my captivity. But actually having a Bible in my hands again—well, you can imagine what it meant. Again and again, I turned to the Psalms, especially Psalms 91 through 120. They were the bread of life that satisfied me as nothing else could.

By this time, too, the guerrillas were frequently asking the spiritual and philosophical questions that naturally arose out of our classes and discussion groups. How do we decide what's right and wrong? Why should we care about the plight of our fellow human beings? Are moral values relative or constant? What assumptions do the major forms of government make about the nature of humanity? Does God take sides in human battles—and if He does, is He on the side of the guerrillas? The questions were endless and challenging. We never lacked for a lively discussion.

It was natural, then, that when the Bible was given to me, many guerrillas started asking me about it—focusing, at first, on issues that directly related to their revolutionary ideals. I was pleased but decided it would be wise to confine religious discussions and observations—including my own worship and Bible study to Sundays. In Colombia, a Roman Catholic country, even the guerrillas assumed that Sunday was a day for “church,” so this arrangement was easy for them to accept. I didn't want to appear too intrusive or “evangelistic,” so when questions arose about spiritual ideas, I'd tell the guerrillas we'd wait until Sunday to talk about that. They seemed to respect this request, and it made all of us look forward to Sundays with a certain amount of anticipation. Each week a few more guerrillas joined me for Bible study, discussion and worship. They even began to join me in prayer.

Not long after that, I decided the guerrillas knew me well enough—and understood my motivations well enough—that I could share some of my personal faith with them when they asked me about it. As I talked about what Christ meant to me, I noticed tears in the eyes of several guerrillas. Amazingly enough, not a single guerrilla—in all the months of my captivity—ever laughed at or made light of my faith. In fact, they were reverent and respectful at it.

Not long after we began these Sunday dialogues, a few guerrillas accepted Christ. These were profound moments in my experience as a captive, moments when God's Spirit manifested Himself so beautifully, so tenderly, that these hardened terrorists often broke down and wept as they received Him into their lives. For me, the most touching thing was that it was not my concept of God they accepted; it was the very real, very personal Jesus Christ who met them within the context of their own experiences, culture, and understanding. I felt privileged to witness it. Incredibly, some of my captors had become my brothers.

It's important to say that my spiritual activities among the guerrillas were never designed to destroy or subvert the guerrilla movement. I never expected that as they accepted Christ they would leave it or turn against their responsables. What I sought was simply to align them with God in a dynamic relationship through the Holy Spirit that would enable them to grow in the knowledge and grace of Jesus Christ and of His Word for the rest of their lives. I felt it was God's responsibility. So I never told guerrilla Christians that they had to leave the movement, although sometimes they asked me if they should. Instead, I told them: “You belong to Jesus Christ now, and you must answer to Him, not to me.”

As weeks passed and more and more guerrillas gathered with me on Sundays for Bible study and worship, I was accused of bringing division to the camps. That happened, not because I was putting the guerrilla Christians into contention with their leaders, but because their transformed consciences naturally led them, as they sought to follow Christ's example, to question the morality of the terrorist acts their leaders expected them to perform.

Their newfound faith was causing trouble—that much was for sure, though that was not my goal. And I'm sure the responsables in many camps must have worried about the close relationships some of the guerrillas were building with me, with good reason. One young Christian guerrilla came to my hammock late at night after hearing that I might be executed soon. He shook me awake and whispered, “Papa Bruchko, I want to tell you that if I am ordered to execute you, I have decided to refuse.” This meant, of course, that he himself would be executed for disobeying an order. “I'm with you,” he said, “even if it costs me my life.”

By this time I knew him, and I believed him. His words moved me deeply. Fortunately, that particular young believer was never asked to shoot me.

By February, when the national-level responsables finally confronted me and insisted I declare myself a committed member of their organization, I knew I couldn't avoid the issue any longer. I explained, very simply, that I could not justify killing to attain social and political goals, so I could not align myself with them. At this point, my classification was officially changed from “political prisoner” to “prisoner of war.”

Prisoners of war, I knew, were always executed. But before they could execute me, the guerrillas would make up a list of “charges” against me, publish them in the national media and then formally sentence me to death for “crimes against the people.” This was their usual strategy.

The charges they came up with were creative. I was accused of murdering 6,100 Motilone Indians; trafficking in cocaine and other drugs; turning Indians into slave labor in my personal gold and emerald mines; working for the CIA; flying helicopters in army attacks on guerrilla camps; and worst of all, of teaching American astronauts to speak Motilone, so they could talk to each other in space without being understood by Russians. This last charge was my favorite. It had a certain romantic ring to it.

As the charges were formulated, other prisoners—mostly kidnap victims being held for large ransoms—were brought in and out of the camps from week to week. I got to know several of them fairly well, and we tried to encourage each other as much as possible.

One of these kidnap victims, a helicopter pilot named Franco, was moved in and out of several camps I was in. We developed a fairly close relationship over the months we were together. Unfortunately, Franco constantly argued with the guerrillas. His belligerent attitude made him extremely unpopular with them. It was as if he were looking for ways to get himself abused or killed.

“Franco,” I'd tell him, “It does no good to argue with the guerrillas. You only hurt yourself. Try kindness.” But he'd fly into a rage, accusing me of “collaborating with the enemy.” Later he'd apologize and say I was right, resolving to keep his anger under control. But it was hard. He was not a person who could accept daily abuse and humiliation without fighting back.

Franco had a complete nervous breakdown after several months of captivity. When this happened the guerrillas, frustrated by his behavior, asked me to become his official “spiritual counselor.” They knew that Franco professed to be a Christian and saw this as a means of keeping him intact enough to collect the large ransom they'd been trying to negotiate for him.

But Franco was not easy to counsel. For one thing, he kept going on hunger strikes. Four of them, all told. “I won't be treated like this,” he told me before the first one. “They can't victimize me. I'll show them—I'll starve myself to death! They won't get their ransom. I still have some power over my own life!” I couldn't persuade him not to do it, so he angrily announced his hunger strike to the guerrillas and was enraged even further when they paid no attention.

By the end of the first night of his hunger strike, Franco came to me saying, “Oh, my friend, I'm so hungry! I can't stand it! You've got to bring me something to eat. Can you sneak me something from your dinner? Don't let the guerrillas know, whatever you do!”

By this time the guerrillas gave me a little more freedom to move around in the camp, so I was able to slip most of my dinner into a plastic bag and hide it under my shirt until I could pass it to Franco later that night. He waited until he was in his hammock and wolfed it down. This went on every day of his so-called hunger strike. And he was always ravenous, so it got to the point where I was starving to death because Franco couldn't get by on less than my full ration of food.

Eventually, the guerrillas started to worry about Franco's health. One of them asked me, “Do you think he might die? How long can he live without food?” Most of the guerrillas had mixed emotions about it—they didn't want to lose their ransom, but at the same time, they fervently wished to be rid of him.

Finally, a responsable came to me and said, “Franco's hunger strike has lasted two weeks now. Can you do something to make him eat? We're getting tired of this. He's driving us crazy. We've decided to just go ahead and execute him if we can't get him to cooperate. After all, he wants to die from starvation, so it will shorten his suffering if we shoot him now.” I decided humor might be the best solution to Franco's problem. “Don't worry about Franco,” I told the guerrilla. “I'm the one who's starving—he's been eating all my food!” The guerrilla laughed uproariously as I described how Franco had been getting plump while I wasted away from his hunger strike. It became something of a camp joke—though Franco never knew about it. After this, every time Franco announced another hunger strike, they gave me two dinners—one for me to “sneak” to Franco to keep him happy, and another for myself. We survived all four of his long hunger strikes this way. Franco was eventually released.

But not all of the hostages fared so well. Many were executed—especially between February and June.

It was during this time, too, that the responsables started to clamp down on me in a concerted effort to force a public “confession” of my crimes against humanity.

I refused. “I've done nothing,” I told the guerrillas. “You're asking me to lie. I have to tell the truth.”

“Then we'll kill you,” they said.

“The truth is a good thing to die for,” I told them. Then I looked each of them in the eye and said, “I can only die once. But you, my friends, will die a thousand times because you'll know you've killed an innocent man.”

After that, the responsables decided to pull out all the stops, trying everything imaginable to break me. I wondered how human beings could subject other human beings to such cruel, inhuman treatment.

They tried to break me psychologically first, using an assortment of ploys. “The Indians have totally abandoned you,” they told me over and over. “We've talked to them, and not a single one of them cares whether you live or die. You might as well save yourself because nobody else will.”

I didn't want the Motilones to make any rescue attempts, of course, but I couldn't believe they would abandon me completely. Surely they remembered our 28 years together. Surely they would continue the work we'd begun in the jungles whether I survived or not; it was, after all, not my work, but theirs, and God's. They could not forget that. As the guerrillas repeated their assertions again and again, however, I began to have small doubts. Was it possible? Had I been abandoned?

But by far the worst moments of my captivity came when I had to watch the executions of the other hostages—people who had become friends. As their bodies were ripped apart by the guerrillas' bullets I was told, “This is what will happen to you unless you sign a confession.” The experience was inexpressibly painful.

The variations of torture the guerrillas invented were remarkable. Many things that happened during this time were so terrible that I will probably never be able to talk about or forget them.

But there were moments as well that will stay with me forever because of their inexpressible beauty. These were not at all what you might expect—not spectacular moments, or even dramatic moments in the normal sense of the word.

Once, for example, during the latter part of my captivity, I suffered a severe attack of diverticulitis—one of several attacks that involved severe hemorrhaging. I lost about two quarts of blood this time, was in excruciating pain, and eventually lost consciousness. When I awakened I was being examined by a doctor the guerrillas had brought into the jungle. He said only a blood transfusion could save my life.

Immediately a fight broke out among the guerrillas over who would win the “honor” of giving their blood for me. A young Christian guerrilla was one of those chosen. After the transfusions were completed, he sat with me for a while. “My blood now flows in your veins, Papa Bruchko,” he told me. There were tears in his eyes. And in mine, too.

Later that night I awakened in terrible pain. I tried to separate myself from it, but this time I couldn't. I was too weak, too exhausted. I felt empty and hollow, and the intensity of the physical pain increased my enormous sadness over the things I'd experienced in the previous months. There was no comfort for me, I thought. None. I had never experienced such total anguish.

Then an absolutely amazing thing happened: A bird known in Colombia as the Mirlo began to sing. I looked up and saw the full moon pouring down through the thick jungle vegetation and felt, inexplicably, that it was shining for me. The Mirlo's song was the most hauntingly beautiful sound I'd ever heard. As I listened, I wondered why it seemed so familiar, why it soothed me so deeply.

The bird's song soared through the damp, moonlit air as I clung to consciousness.

The music was incredibly complex, set in a minor key. The notes never repeated; they reminded me more and more of something achingly familiar, something comforting—but I just couldn't put my finger on it. An ancient Aramaic chant—was that it? Yes, it was reminiscent of that—but why did it make me think of the resurrection of Christ?

The familiarity puzzled me, but I had no real need to understand it. The music was the most exquisite I had ever heard; I was sure of that. It was communicating something profound to me, something I needed desperately but couldn't identify. I let the song carry me for a long time. Then I lost consciousness again.

When I came to, the bird was still singing. I wondered whether I might be hallucinating. After all, everyone knew Mirlos never sing at night. And I was desperately ill, barely hanging on to life. It wouldn't be unusual to hallucinate in my condition. But what I was more intent on trying to understand was why this song—real or imagined—was having such an amazing, restorative effect on my spirit. I could feel myself coming back to life with each note.

Then, as the bird's song continued to penetrate the quiet night air, I knew: I knew why this song seemed so hauntingly familiar, why it spoke to me of the resurrection, and why it comforted me like familiar, loving arms. The Mirlo was singing a Motilone minor-key tonal chant, mimicking the traditional sounds with such amazing accuracy that I could almost hear their words, could almost see my friends Kaymiyokba and Waysersera and all the other Motilones I loved, singing the prophecies of the resurrection of Christ in the timeless Motilone way, our hammocks swaying together in the rafters of a communal home in the jungles as they had for the 28 years I'd lived among them. I could almost feel their warm, reassuring hugs.

At that moment I was lifted above my agony in a way I'll never be able to describe adequately. I didn't even care whether it was real or imagined. The Motilones were with me; I knew it now. I had not been abandoned. And I was going to survive to be with them again because God had used Mirlo's song to transfuse His lifeblood into me.

One of the guerrillas walked over to my hammock as I opened my eyes at dawn. The pain was subsiding a little.

“So,” he said softly, “how did you like your personal concert last night?”

I questioned him with my eyes. “The Mirlo,” he said. “His song kept us awake all night long. We've never heard anything like it! The boys wondered whether it was a special angel sent to sing for you. Did you hear it?”

One day in July I was brought before a responsable and told that since I could not be convinced to sign a confession, I would be executed. He gave me three days to prepare myself for death.

There was nothing special I needed to do, I told him, so why didn't they just get it over with? I was ready.

But no, I had to wait the full three days. So I spent them doing exactly what I'd been doing for nine months—teaching, cooking, going about daily life as usual. The guerrillas watched me closely during this time. I wondered what they were thinking.

By this time about 60 percent of them were Christians. The responsables would have a hard time finding someone to shoot me. Even those who weren't Christians had become my friends. I worried about them but knew that God would complete the work He had begun in all their lives. I had done what I came here to do, and I would die without regret.

On the day of my execution, the responsable ordered me tied to a tree. They read the formal charges against me and declared that I had been sentenced to death by the “people's court.” I didn't want to be blindfolded. I looked into the faces of my executioners and saw that many of them had tears in their eyes.

Then they raised their rifles and the order was given. Shots rang out. I waited for the impact of the bullets. But I felt nothing.

The guerrillas looked at me with amazement. Then they examined their rifles and said, “These are blanks!”

It had been one final attempt to break me. But it hadn't worked.

The next morning Federico, one of the guerrilla leaders, came to me and said, “Bruce Olson, I have good news for you! You're being released. Are you happy?”

I shrugged. “I'm indifferent,” I said. “My concern is for the Motilone people, the solidarity of their territory, and the continuance of the programs that are so vital to their future. What about them?”

“Yes, yes, we understand your commitment,” Federico assured me. “We made an error when we kidnapped you. The charges against you have been dropped. It's an embarrassment to us that you've been held in our camps. If we've mistreated you we hope you can find the greatness within you to forgive us. We've decided to leave the Motilones as an autonomous people. We will leave them alone, and you may continue your work among them as before.”

I was incredulous. “Are there conditions to my release?”

“You are released without conditions,” Federico said. “Now are you happy?”

“I am, indeed.”

Federico's eyes actually filled with tears. Then he hugged me.

Two weeks later, after a long trek back to civilization through the jungles and rivers, I was finally released. That's when I discovered, to my total astonishment, that the whole world seemed to know about my captivity.

The Motilone people and all the other Indian tribes in Colombia had joined hands in support of “the man who is our brother, our friend,” threatening total war with the guerrillas unless I was released. And the media had taken up their cause, running hundreds of front-page stories in every newspaper in the nation. The entire Colombian population had then followed suit, rising up as a single voice to denounce the guerrillas for what they were doing.

“How can these criminals claim to speak for 'the people' and then kidnap a man who has done more for the indigenous people of this nation than anyone else?” they asked. “It's an outrage!”

The presidents of both Colombia and Venezuela welcomed me back to the world. “You are a national emblem,” President Barco told me. “For the first time in history, Indians defended a white man. Their cause has united the Colombian people and given them the courage to fight against the tyranny of terrorism.”

Shortly after my release, the Motilones organized a meeting with leaders of all the other Indian tribes of Colombia. Together, they issued an ultimatum to the guerrilla forces and drug traffickers operating in their lands: “You have until December to clear out. If you don't go, you will be at war with all 500,000 of us.” The guerrillas' numbers are small, though their weapons are large. War with the Indians would be a no-win situation. I think they will have no choice but to leave.

In the weeks since my release, the drug war has exploded in Colombia. I've followed the news of the deaths and wholesale destruction with great sorrow. But I'm also filled with pride. The Colombian people show a new determination, it seems, new courage to stand up to the drug lords of the Medellin cartel.

Why is it only now—after all the years the drug lords have been able to do whatever they liked in Colombia—that the people have decided they will fight back?

I remember the people on the streets of Bogota who welcomed me home saying, “We're inspired by the example of the Motilones and their courage. We will no longer tolerate these criminals out of fear for our lives. We'll stand up to them!”

I don't think it's a coincidence that this is exactly what's happening in Colombia at this moment. Perhaps the Motilones' part of God's orchestration in Colombia will not be noticed by many, but I believe it is real and significant. I pray that it will continue.

Several people have told me since I've arrived in the States, that my release was the greatest victory they'd ever experienced. This surprised me. Naturally, I'm thankful for many things—especially that I'm alive and free to continue my work among the people I love. I'm thankful for the guerrilla lives that now belong to Christ and will continue to be conformed to His will. I'm thankful, too, for the oneness of spirit that's drawing the people of Colombia together for the first time in many years. These are victories, of course. And there are many others I could mention.

But for me, the greatest victory of all lies in the sweetness of the moments when I caught glimpses of the “subscript” in God's complex orchestration of lives and events. In those moments I knew that He was quietly working out His sovereign will, not only in my life, but in the lives of everyone involved: the Motilones and other tribal peoples, the people of Colombia, the guerrillas, and indeed, as I'm now discovering, people all over the world.

In those moments, I knew—even before my captivity ended—that the greatest victory of this long drama would not be found in my release. It would be found, instead, in the song of a Mirlo in the moonlight.

Bruce Olson has been a missionary to the Motilone Indians in Colombia since 1961.

Possessing the Gates of the Enemy

By Cindy Jacobs

Chosen Books, Grand Rapids, MI

The Language of Intercession, pages 108/111

Loosing

Loosing in prayer is a type of intercession that sets the captive free from the hands of the enemy. Let me give you an example from an intercessory team and end with an examination of the techniques used in the example.

The intercessory team at the Lausanne 11 Congress on World Evangelization, held in July 1989 in Manila, was gathered for a prayer watch. Prayer warriors like Robert Birch, Ben Jennings of the Great Commission Prayer Crusade, and Joy Dawson prayed along with other mighty prayer giants gathered there who, with swords honed from years of warfare, cut quickly through Satan's devices. There were several requests about which we were praying when a special one came through for a missionary named Bruce Olson. To understand the importance of this request, it is important to know the scope of what God has done through Bruce Olson.

Bruce Olson is a missionary to the Motilone Indians in Colombia. His life has been a well-known encouragement to those God calls to the missionary field. He had gone to the field at the age of nineteen with no prior experience as a missionary but with a deep call from God. His first attempts at reaching the Indians almost cost him his life as the Motilones had the dubious distinction of killing everyone who came near them.

After years of reaching out to the Indians, learning their language, and refusing to give up, Bruce had seen many of the Indians come to the Lord; he has also brought much good by introducing methods of farming, health care, and education.

The knowledge of his prior sacrifice was in our hearts as we listened to the request: Bruce Olson had been captured nine months before by enemy guerrillas who wanted to use him against the Indians. The guerrillas had issued a statement that Bruce Olson would be killed.

We received this request with a sense of gravity. We knew that it was not an idle threat, as others had already been killed by the group. We were also aware that Bruce was ready to meet the Lord, but this did not seem like God's time for him to go home. As we went to prayer each of us sensed that the Lord wanted to stop the guerrillas and use Bruce further in ministry. The enemy had to be halted and the captive loosed.

It was Wednesday afternoon, July 12, 1989. Joy Dawson was asked to lead the group in prayer for Bruce. Joy is a general's general in God's army and has a no-nonsense approach to intercession. She is a petite, lovely former New Zealander with expressive green eyes. Joy stood and waited on God before praying anything. During those moments I felt that God was poised for action and that we were about to participate in it.

She started by praising and thanking God for His sovereign and complete control over the situation. Following this, she committed Bruce into the hands of God and declared her trust in Him that He was acting on Bruce's behalf. She then asked God to do something to bring the maximum glory to the Lord Jesus in this situation with Bruce and his captors and released faith that this prayer would be answered.

Next, she asked God to dispense ministering angels to Bruce and to keep his mind in perfect peace.

Joy stood in the gap between Bruce Olson and satanic forces. The intercessors were in agreement as she began to war in the heavenlies with the authority that comes from knowing she had a right given by the heavenly Commander-in-Chief to do so.

She wielded the sword of the Spirit boldly by binding the forces of darkness operating against Bruce Olson according to Matthew 18:18 - “Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven.” She then declared the shed blood of the Lord Jesus as the grounds for Satan's total defeat and she exercised faith in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ loosing Bruce Olson from all of the enemy's power and plans. She concluded by praising God for His almighty power and plans that were in operation.

I did not hear the story of Bruce Olson's release until after returning home from Manila when I received a Christian magazine that carried a story about him. As I read the article and saw the date of his release, I was deeply touched to find that it occurred exactly one week after the intercession that took place in the prayer room in Manila. We know that many, many people had been praying those nine months for his release but felt that the intercession on that particular day helped to loose a captive to fulfill the destiny of God upon his life.

This is also an example of using both binding and loosing in order to accomplish the desired answer. The intercession first prohibited or forbade the guerrillas from killing Bruce Olson, who was then permitted or allowed to go free through the prayer.

A loosing prayer can have the following effects:

It can actually cause the physical release of a captive as in the case of Bruce Olson.

It can release a person from sickness or disease as in the case of the woman whom Satan had bound with an infirmity.

It can loose or declare the will of God to be done in a certain situation.

It can loose God to move in and change situations. The Word of God says, for instance, that He has chosen to move into needs that we have presented in prayer: “He saw that there was no man, and wondered that there was no intercessor” (Isaiah 59:16); “You do not have because you do not ask” (James 4:2).

To sum up binding and loosing, we could say the following:

Binding stops the enemy's attacks.

Loosing releases or permits God's will to enter the situation because God has willed that His purposes be carried out by asking in prayer.

I hope these scriptural precedents and examples help you better understand the language of intercession and think through its application. Let's look now at another misunderstood aspect of intercessory prayer, one that may seem to depart from rational thinking because it calls on our emotions.

The Motilone (Barí) Miracle

A Christian missionary to be proud of...

By Faith Annette Sand

Normal noises filled the jungle afternoon—cicadas beginning to announce that evening wasn't far off, birds singing then sweeping over the river in pursuit of fish attracted by lazy flies. The monkeys were out of eyesight, but you could hear them chattering in the tall trees just beyond the clearing.

The changing of the guard from diurnal crew to nocturnal gang was definitely underway when the putt-putt of a motor broke through the idyllic green. I turned to Jairo, my fifteen-year-old Motilone guide, and asked, “Does that sound like the Iquiacarora boat coming upstream?” He thought it did.

I hurried to the river landing and watched the long dugout round the bend and get larger on the horizon. As it approached, I saw one blond head—the head of the person I was looking for—seated amidst a dozen black-haired people. I waved at the boat as it came alongside the landing, and the Motilone pilot deftly turned the canoe towards the shore.

Bruce Olson had been a hard person to find. After flying over the Andes to Cúcuta, a town in northern Colombia on the Venezuelan border, I had boarded one of those buses where suitcases are loaded on top while pigs and chickens come inside with their owners. We bumped five hours over washboard roads before arriving in Tibú, an oil town whose dusty streets are slicked down with a refinery by-product. (It keeps the dust from flying—but makes every step a trifle precarious.)

In Tibú, the Motilones maintain a large house where any tribal member can stay while being treated at the oil company's hospital. I had been telephoning this house for days, trying to get some information on Bruce's whereabouts. Each time, however, I had found myself speaking Spanish to a woman who understood only Motilone.

Finally, hoping to do better with sign language, I decided to make the trip to Tibú anyway. And to my relief, when the Motilone woman came to the gate, she smiled broadly—and went to call Jairo, a bilingual high school student who had just arrived from the jungles.

Jairo not only spoke good Spanish; he knew Bruce's itinerary. Best of all, he was willing to guide me to where he thought we could intercept Bruce the next day. I would find him on the river, said Jairo, making his circuit, visiting the villages, tending the sick.

Unfortunately, the pickup I needed to ride in for the next leg of the trip made only one trip a day—at six in the morning. Bright and early, Jairo and I crowded into the back end of the '42 Ford, which featured a plank down each side for first-class seating. (The unlucky hung on behind or dangled off the running board.)

The road followed an oil pipeline, which headed into the interior in a pretty straight line, up and down very hilly terrain. The Andes were nowhere in sight, but it was easy to see that we were on their tropical foothills.

After a breezy four-and-a-half-hour ride, we came to the River of Gold (named by some hopeful explorer). There we hired a Colombian boat to take us upriver another two and a half hours, where we were dropped at the home of a Motilone. It was there, in that idyllic jungle setting, that I waited to see how accurate the jungle telegraph really was.

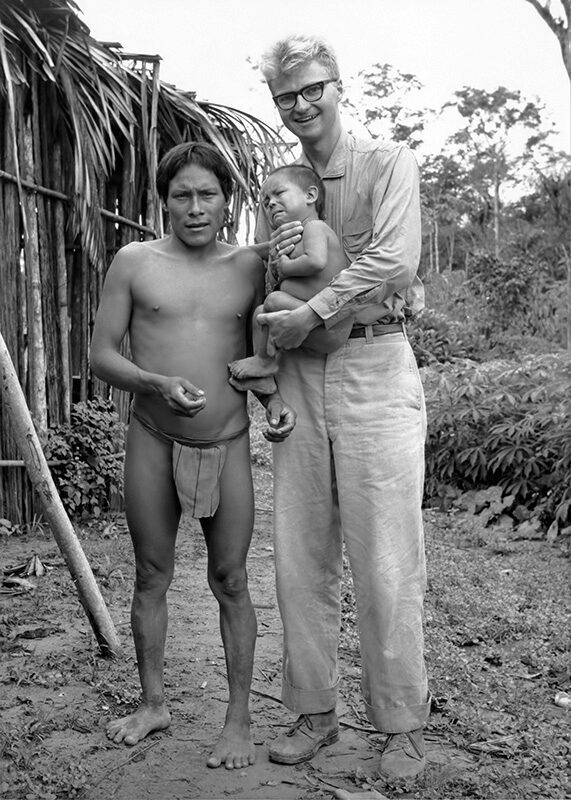

As Bruce stepped out of the dugout to shack my hands, I felt like an accomplished scout who had just flushed a long-sought prize from its jungle habitat. I wanted to say, “Dr. Livingston, I presume?”—but I wasn't sure he'd understand.

The disparity between Bruce's tall Nordic frame, and the short, sturdy indigenous Motilones was the first thing I noticed. Yet his ease in communication with them and their naturalness with him somehow made him fit into their world.

“You feel like a Motilone to me,” I said as we walked toward the house.

“I will never really be a Motilone,” he answered. “I will always be different from them. Yet I know I will never again feel fully comfortable in the culture where I was raised.”

After having spent eighteen years in Latin America, I could relate to these feelings. To become a missionary is to give up not only the homeland but also the feeling of belonging in the homeland.

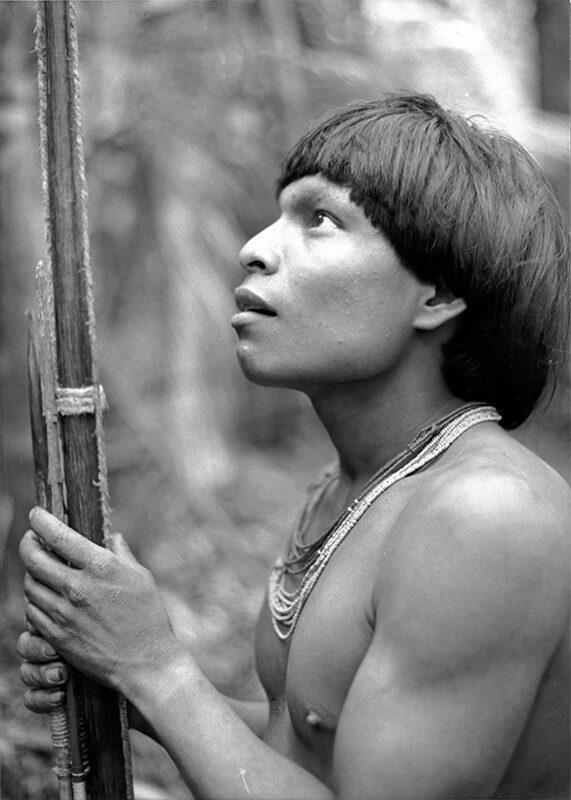

And the Motilone are certainly an admirable people to give yourself to. They are calm, soft-spoken, curious, and exceptionally gentle with their children. They are also generous and pleasingly content with their rather primitive existence. Bruce, I found, had taken on many of these Motilone characteristics in the two decades he had lived with them.

After that first meeting, we talked for nine hours nonstop. We talked through supper, through a one-and-a-half-hour boat ride to Iquiacarora, and for many hours after. Sitting in front of a clinic he helped establish, watching the full moon make its way across the sky, Bruce told me the story of how he came to work with the Motilone tribe.

Later he invited me to accompany him for a few days as he made his rounds, to give me a better feel for the Motilones and their world. I eagerly accepted, wanting to see for myself the amazing success this dedicated Christian missionary has had in helping to preserve the Motilones' traditional lifestyle while assisting them in a rather traumatic transition into the modern age.

The next day, Bruce and I waded through streams and squished along muddy jungle trails. Exotic vines dangled in our path, with thousands of varieties of orchids and flowers painting a serene beauty.

Yet in the midst of this beauty came the loud cries of tropical birds and screeching monkeys. Each of these creatures seemed to protest harshly our invasion of its turf.

As we plunged deeper into the Motilones' traditional land, I couldn't help but reflect on how much like the birds and animals of the jungle these indigenous people are. Living in amazing harmony with their tropical environment, they have been for four hundred and fifty years a territorial people. Following the laws of the jungle, they have done all in their power to keep foreigners off their turf.

Spanish conquistadores, dreaming of fabulous gold mines, made a mule trail through Motilone territory and established a settlement as a local power base. The ruins of a sixteenth-century Spanish chapel are still extant—a silent witness to how the cross accompanied the sword into the New World. (European churches are still filled with gold objects sacked from the indigenous peoples of Latin America.)

That the Motilones refused to be plundered is a testimony to their own feelings of self-worth. The Spaniards who settled in the Catatumbo River valley—which funnels water from the Andes down to oil-rich Lake Maracaibo—never made it back to Spain. They were massacred as they caravanned back to the coast. The gold bullion which they dropped has been swallowed by centuries of jungle growth.

The lesson of the Spanish invaders was never forgotten by the Motilones. They began killing everyone from the murderous and stealing “white” race who invaded their territory.

Until Bruce Olson.

It still isn't clear to them why they spared the life of this young Minnesotan who felt the so-called-of-God to bring them the message of Christ. Indeed, they shot him in the leg with an arrow when he first ventured onto their lands. But as a tall, gangly, blond youth, he didn't look much like a normal oil prospector or a Colombian land poacher. And he had a strong body which didn't succumb to the fever and infection which set in his leg.

Perhaps it was all part of God's providential care for the Motilone. Perhaps God knew that the tribe was reaching the end of its ability to fend off the invader. Their homeland was surrounded by Western oil companies, mineral prospectors, and land developers. People in the area remember how planes from the “outside world” firebombed the traditional Motilone longhouses, trying to force the Motilones to move off their oil-rich land. Remaining isolated and protected from the greedy outside world was no longer possible.

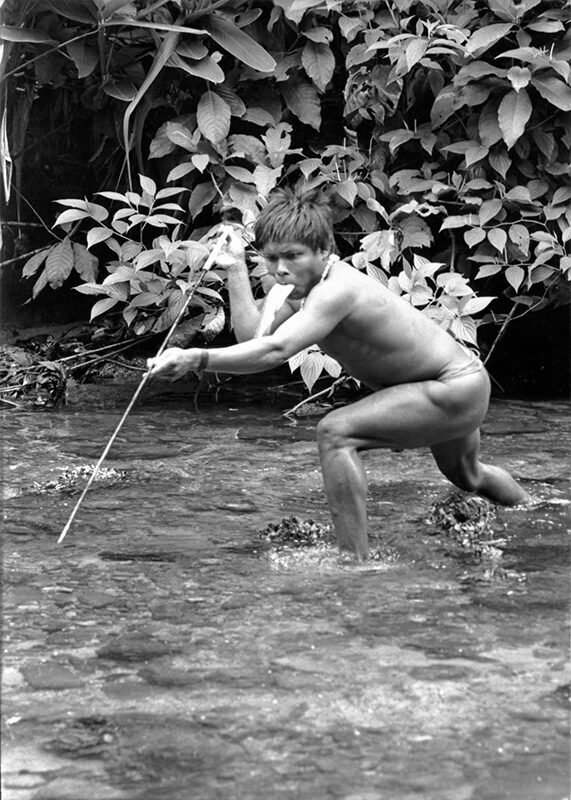

The Motilones, despite their cannibalistic reputation, are people who, at least in their exotic jungle environment, largely live at peace with each other. During his [thirty-eight] years with the tribe, Bruce has seen little homicide, drunkenness, prostitution, or physical violence. Not only do they have a true sense of belonging to one another in the community, but they also immensely enjoy life together in their habitat. Everything they do is made into a sport. Hunting, weaving, fishing, grinding, collecting the earth's produce—all of these become part of their happy modus vivendi.

That first morning, for example, Bruce and I joined a group of Motilone on a nearby river. The early birds had enclosed a U-section of the river with a stone dam reinforced with broad leaves that looked like banana leaves, but much stronger. This gradually dropped the water level in the U, exposing the fish. The fish were speared with long, thin shafts which the Motilones sharpened after each thrust with knives held in their teeth. After a couple of hours, some men had fifty or sixty fish strung on their vines which they trailed in the cool water.

The day took on the feeling of a Fourth of July picnic. Children happily grubbed crabs under the rocks along the mud banks. Women collected and wrapped the fish in broad leaves for carrying home. And the men competed fiercely.

The celebration fervor seemed complete when the men decided to line up along the jungle trail—old men at the front on a handicap basis for a foot race home. (Chieftains in the tribe usually are the best hunters, fishers, and runners!)

During the dry season, these fishing expeditions occur three or four times a week. During the rainy season, the Motilones hunt with the same intensity. Incredible to think that every day is made into such a lark!

That day's fishing expedition, however, was marred somewhat, when a nine-year-old boy got too close to someone wielding a knife and was gashed in the leg. A sturdy young warrior carried the by piggyback to the clinic at Iquiacarora, where Bruce deftly put nine stitches in his leg.

“How do you account for all the skills you've managed to acquire without standard credentials?” I asked. “You've hardly even been to a university.”

“The Motilones were willing to accept me and knew I was here to help”, said Bruce. “And because I was the only one with any contact with the outside world, I felt obligated to read and observe and ask questions whenever and wherever I could so that I could provide the necessary services. Of course, it has been God who has helped me guided me, and taught me.”

Besides having the gift of truly enjoying their way of life, the Motilone are also religious people, concerned with pleasing God. Their mythology recounts how the knowledge of the trail that led them to God has been lost because of evil antecedents. Even before Bruce arrived, they knew they had broken communication with their Creator. And they knew they needed a special revelation to show them the way to the horizon where their God was to be found.

Some people consider the Motilones very lucky people. Or perhaps the Motilones have simply pleased God through their earnest desire to find the trail that would lead them back to their Creator.

In any case, God—who seems to prefer using the weak and foolish ones of this world to confound the wise—decided to send to the Motilones a lankly, nineteen-year-old, blond Scandinavian-American. Bruce Olson had no qualifications, at least none which would attract the attention of any established mission organization. But with the simplicity and trust of the young, this ingenious, half-trained linguist left college in the middle of his studies to head to Colombia. All he knew was that God had “called him” to go to the Motilones. (The story of how he was almost killed but then spared to live among the legendary tribe is recounted in his book Bruchko.)

When he first went to South America, Bruce's well-to-do family and various mission organizations expressed distress at his intentions. He was told he had neither the education nor the experience to prepare him for such a venture. And when Bruce responded that he knew God was leading him to do this, they were angered by his insolence..