From Charisma and Christian Life Magazine, Lake Mary, FL.

HOSTAGE! PART ONE

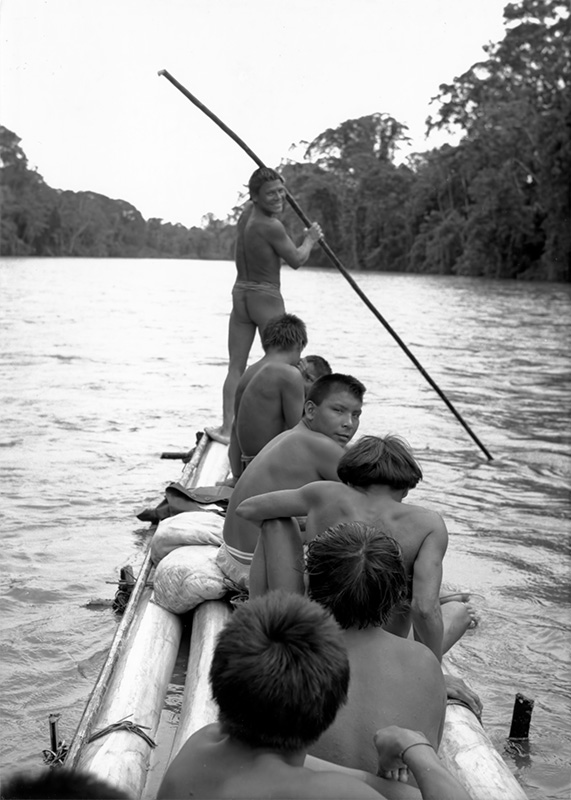

The hot sun beat down upon the equatorial jungles of northeastern Colombia known as “Motilandia.” It was a steamy, 100-degree October morning. Exotic birds screeched, monkeys screamed and a chorus of katydids assaulted my ears as I headed toward the dugout canoe that waited on the bank of the Rio de Oro to carry me and 15 Motilone Indian companions down-river from Iquiacarora to Saphadana, the site of a Motilone food cooperative. I walked slowly, enjoying the company of the Indians and savoring the sounds; of chattering jungle creatures in the lush greenery surrounding us. I was never in a hurry to leave Iquiacarora.

As I climbed into the canoe, I glanced at Kaymiyokba, one of the Motilone leaders who had become my close friend over the 28 years I'd lived and worked among his people. He grinned, starting up the outboard motor while the other Indians took their seats. His warm smile filled me with a deep sense of satisfaction and belonging. We were family, he and I. The people crowded around me were my brothers and sisters. I was truly at home and exactly where I belonged on planet earth. The thought filled me with a mixture of quiet contentment and nostalgia.

How could I have imagined, when I first walked into the jungles of Motilandia in 1961, all that God intended to do here? How was it possible at I had left my family and friends in Minnesota at the age of 19 to go on a journey that would lead to such an exotic place, and to these amazing, legendary people a —people so isolated and hostile that no white man had survived contact with them in 400 years of recorded history until I walked into their territory?

When I boarded the plane for South America with nothing but a one-way ticket and a few dollars in my pocket, not knowing one word of Spanish, nearly everyone had thought I was crazy—or just plain foolish. But I had been unable to resist the subtle, persistent longing that had drawn me here, the growing love that God had put in my heart for the indigenous tribal people of this continent, the quiet voice inside that told me I would never be happy, never have a moment's peace, until I obeyed His call. No, I could not have imagined where that call would take me; I could not have imagined that today my heart and my life would be deeply rooted in these people and in this vast, remote jungle.

Nor could I have imagined that this day, October 24, 1988, would be a day unlike any other that I had spent in these jungles, that it would be the first day of a 9-month ordeal that would leave me—and indeed, a whole nation—profoundly changed.

It was a good day for travel. The rainy season was upon us, but the sun had broken through and I was glad to see it, even though it would turn the jungles into a giant steam bath. I'd been feeling another malaria attack coming on, and the intense, sweltering heat of our down-river journey just might sweat it out of me—or at least keep my teeth from chattering for a while.

As Kaymiyokba steered the boat, I scanned the shorelines on both the Colombian and Venezuelan sides of the river, watching for any guerrillas who might be lurking there. The four major guerrilla organizations in Colombia had operated in adjacent territories for nearly 12 years, gradually controlling more and more of the area surrounding Motilandia. Guerrilla strategists were avid students of revolution in other parts of the world; the Sandinistas' failure to occupy and control Mosquito Indian tribal lands in Nicaragua had been a serious error, and Colombia's guerrilla strategists had learned from their mistake. My life had been threatened repeatedly because Colombian revolutionaries saw me as the key to controlling the vast Colombia-Venezuela border territory belonging to the Motilones. I was, in their eyes, so influential among the Motilones and other neighboring tribes that unless I could be convinced to join their revolutionary movement and bring the Indians into their cause, the Indians would be a constant thorn in their flesh. Since I had resisted their previous attempts to recruit me, I'd been marked for elimination. With me out of the picture, the guerrillas theorized, the Indians would soon yield to their demands. They would then have free rein in northeast Colombia—and the success of their revolution would be assured.

All of this had made me cautious in my journeys through areas like Saphadana, where the guerrillas seemed to be making their presence known with increasing boldness. I was not fearful for myself so much as I was fearful of the bloodshed that might result among the Indians if I were killed. The guerrillas were capable of anything. I had known many of them over the years, including some of their leaders—a surprising number of whom were former pastors, priests, and students from mission schools in the area. I had even tried to convince a few to redirect their idealism toward positive, humanitarian social service goals instead of revolution, but without much success. These were dedicated terrorists who had learned to rationalize their kidnappings, executions, bombings, and other crimes by claiming they served a higher cause: “The people's revolution.”

Now, as we journeyed downstream, I felt tense. Everyone else seemed in good spirits, so I tried to relax. After an hour and a half, I caught a glimpse of the shoreline at Saphadana, immediately noticing two guerrillas standing in a clearing a short distance from the boat dock. They carried rifles and machine guns, and they were watching us intently.

Victor, the Motilone sitting next to me, leaned over and whispered, “The guerrillas are looking at us.” He exchanged nervous glances with Kaymiyokba.

I avoided looking in the guerrillas' direction. While Kaymiyokba docked the canoe I deliberately turned my back on the guerrillas as they walked toward us. I was about to climb out of the canoe when, without warning, a spray of machine-gun fire pelted the water around us.

“Out of the canoe!” one of the guerrillas shouted. They were still about 30 yards away. We climbed out, and the Indians started toward the guerrillas, obviously intending to attack them with their bare hands. But one of the guerrillas fired another volley in our direction, this time slamming into the motor and ripping a gaping hole in the side of the canoe. “Lie down with your faces to the ground!” he ordered.

Kaymiyokba continued to walk toward the guerrillas. I could see that he was struggling to control his anger. “Let's discuss this,” he said in Spanish. “Let's not start something we'll all regret...”

“There's nothing to discuss!” the guerrilla shouted, spraying the dock area as punctuation. One of his bullets grazed Kaymiyokba's forehead. The Motilone stood his ground.

“Bruce Olson is taken captive by the Camilist Union-National Liberation Army!” the guerrilla shouted, motioning at me to step toward him. This guerrilla group, commonly known as the ELN, was the only one of the four largest national revolutionary organizations that had not agreed to an informal truce with the Colombian government after being offered the opportunity to put their agenda before the people in free elections.

I assessed our situation, realizing I had only a few seconds to make a decision. There was no way we could successfully resist these men in physical combat; I could safely assume there were more armed guerrillas hiding in the trees, and we had no weapons whatsoever, not even Motilone bows and arrows. I never carried arms, and on this trip I hadn't even brought along a pocket knife—not that it would have been any help against military weapons.

I quickly reviewed other possible options. I could jump in the river and swim underwater to avoid the guerrillas' bullets, and probably escape downstream. I knew the area very well; the guerrillas did not, so my chances would have been good. But that would have left the Motilones at their mercy, so I couldn't risk it. And it would only put off this moment to another time, another place.

As the guerrillas trained their guns on me, I decided that the moment had come to face the enemy. But I would try to do it on my terms, in a way that would catch the guerrillas off guard and give the Motilones their best chance to escape unharmed.

I picked up the backpack I'd dropped when the gunfire had started and told Kaymiyokba in Motilone, “Don't follow me! Don't do anything!”

Then I spoke to the guerrillas: “I'm Olson,” I said. “I'm the one you want. Leave the Motilones alone.” I turned and began to walk away from both the guerrillas and the Indians.

By the time I'd walked a few yards, about two dozen more guerrillas materialized out of the jungles. I ignored them and kept walking, hoping to put as much distance as I could between them and the Indians. Then someone shouted, “Stop! Stop or we'll shoot!”

I kept walking faster and faster, shouting at them over my shoulder, “You came to capture Olson. You can have me, but you'll have to come and get me!”

The guerrillas started after me and I began to walk as quickly as possible without actually running. Finally, when we were about 500 yards from the Motilones and all the guerrillas had abandoned the Indians to chase me, two more guerrillas suddenly appeared in front of me. Using their weapons, they knocked me to the ground and roughly forced my face into the wet earth. One of them put his gun to my head.

So this is how I'll die, I thought. A bullet through the brain. I was surprised that I felt rather calm.

As I waited for the trigger to be pulled, the other guerrillas arrived, all of them very nervous and excited. “He's very dangerous! Careful!” someone shouted. “Don't take any chances! Don't let him move!” Everyone talked at once, breathing hard, working fast. My hands were yanked behind me and bound tightly with a nylon rope. This is amazing, I thought. Who would believe this? They're afraid of me!

I was dragged to my feet and about 30 guerrillas closed ranks around me, ordering me to walk. I was relieved to find that we were headed away from the Motilones, who continued to watch from a distance, obeying my order to do nothing. I moved as quickly as possible, praying that they would not decide at the last moment to put up a fight. They didn't.

The guerrillas pushed me steadily through the wet, tortuous jungles, first on foot, then by canoe, and finally on foot again, for three days and nights until we arrived at a location they'd decided would make a relatively safe first camp. I knew exactly where we were most of the time; it was territory I'd traveled to many times during my 28 years in the region. I was thankful that if I had to be kidnapped, it would be here, on home turf. It would have been truly horrible, I thought, to be captured in a city, taken to a strange, unfamiliar place, and locked in a small room. At least here, in the high Catatumbo, I was in the place I loved more than any other spot on earth, the place I knew God wanted me to be.

If I had to die, this was where I wanted to do it. I wouldn't have a single regret. It was ironic: Here I was, in the hands of ruthless terrorists who were probably going to execute me shortly, and I was feeling quite pleased and comfortable with the situation because I knew—beyond all doubt—that I was exactly where I belonged at that moment. This certainty would stay with me throughout the ordeal to come.

In all of the 12 camps, I lived in during the nine months of my captivity, I would be guarded 24 hours a day by at least two heavily-armed men. The guards were usually changed every hour, so there was no possibility that one might fall asleep or become too relaxed in my presence. Much of the time my hands were kept bound behind my back, even when I was very ill and in extreme pain.

The rains were relentless and demoralizing. A crude makeshift shelter was constructed over my hammock in the first camp, but it offered virtually no protection from the elements. I was always soaking wet, even when the rain let up for a few hours, as it did only occasionally. It was so humid, even on sunny days, that shoes and clothes never could dry.

During the two weeks, I spent in the first camp, I tried to remain quiet and spend as much time as possible resting to give my body a chance to recover from malaria. But the attack continued and then, just as I thought I was recovering, came back again, probably as a result of the conditions I was living in. I knew malaria wouldn't kill me, but the disease has a way, sometimes, of making you almost wish it would. Yet it wasn't unbearable. I had learned years before, when I had injuries and illnesses in the jungles, to separate myself from the physical discomfort. When you're miles from help and your arm or leg is dislocated on a jungle trail, you can't sit down and agonize over it. You have to keep going. I'd say to myself in such moments, “I'm in pain, yes, but this pain only exists in my body. I am not my body. My mind and spirit are above this, not part of it.” This technique worked for me, and I would use it to get through some of the worst experiences of my captivity.

It may seem bizarre to some people, but the truth is that it never once occurred to me that it was God's responsibility to rescue me miraculously from this situation. Instead, I believed it was my responsibility to serve Him right where I was. What I asked of God from day to day was very simple, very practical, and I suppose quite typical of me: Father, I'm alive, and I want to use this time constructively. How can I be useful to You today?

This was to be my prayer, as well as my “strategy,” throughout the long months of my captivity. But it was nothing new; it was how I approached every day of my life. Why should my prayers or my outlook change now, just because I was in the hands of guerrillas? I knew that God was subtly orchestrating His plan in the jungles—not only among the Motilones and the other 14 tribes we'd been working with but also among the guerrillas. I assumed that this situation was part of that orchestration, and I wanted to be open to whatever God might have in mind. I've always felt that I could serve God in any situation, and this one was full of intriguing possibilities. As a result, I wasn't terrified or even particularly anxious about my fate. I knew it was God—not my captors—who would control the outcome of the situation.

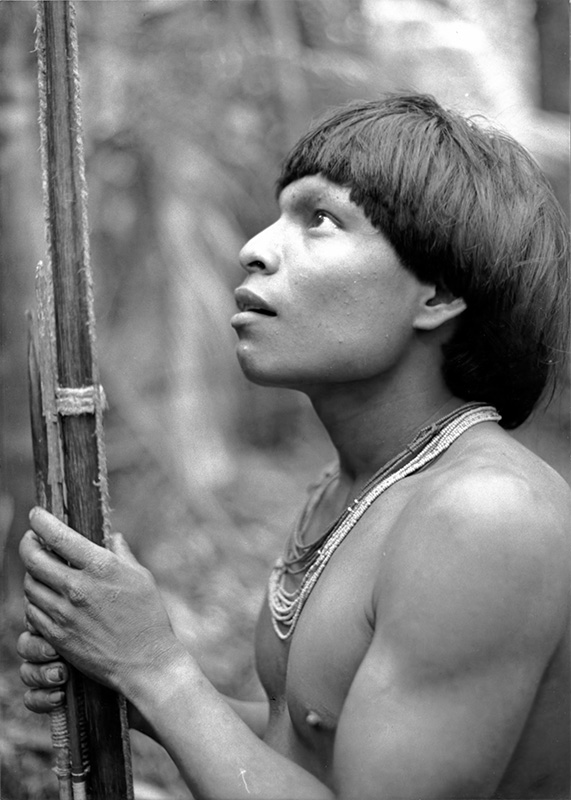

When people ask me now, “How could you believe that God was in control when you were in such a horrible situation?” the best way I can answer is to tell a story about something that happened during my first years in the jungles when I was out with a Motilone hunting party.

Our intrusion into the jungles had brought the usual reaction from assorted birds and monkeys that day, but as we quietly slipped through the dense undergrowth I noticed a sudden escalation in the volume and intensity of the cacophony. Millions of katydids joined the animal squawks and screeches, raising the noise level to the point where our human voices were nearly drowned out. I'd never heard anything like it.

Astonished, I'd turned to a nearby Motilone and shouted, “Listen to that! Isn't it incredible?”

The Indian had nodded his agreement. “Yes,” he'd called back, “We heard it too. It's a piping turkey!”

His remark had stopped me in my tracks. A piping turkey? All I'd heard was chaotic, ear-shattering racket! How could anyone notice the voice of one lone turkey in the midst of this din?

The Motilone had seen my confusion and had signaled me to stop and listen quietly. When I did, it took several minutes before I began to pick out which sounds were which—animals, birds, insects, humans. Then, slowly, the separate voices became more and more distinct. Finally, after more patient listening, I heard it. Behind the hue and cry of the jungle, behind the voices of my companions, behind the quiet sound of my own breathing, was the haunting, reedy voice of the piping turkey, sounding for all the world like it was calling to us from inside a hollow tube.

It had been a poignant moment for me, a moment that had spoken to me of much more than the Motilones' highly developed sense of hearing and my own lack of auditory discrimination. It had made me wonder what I'd missed—not only in the jungles but in my own spiritual life. How much had I overlooked when I'd failed to patiently “tune in” to God's subtle voice in the midst of life's clamor and activity?